“At the age of nineteen, on my own initiative and at my own expense, I raised an army by means of which I restored liberty to the republic, which had been oppressed by the tyranny of a faction…”

— Res Gestae Divi Augusti, “The Deeds of the Divine Augustus”

***

Though Stoner is what he’s famous for today, Augustus is what won John Williams the National Book Award in 1973. When I read both books this past fall (and within weeks of each other), I recall haranguing more than a few friends about them. They’re basically perfect novels.

As a prospective academic, maybe I was destined to love Stoner. And as “something of a history buff”, maybe I was just as predisposed to Augustus. The latter’s themes and images have stayed with me months after I first absorbed them, acquiring a personal significance I’m still trying to understand.

So instead of dissipating my thoughts on Augustus in conversation—which, sadly for you, dear reader, I couldn’t help but do for Stoner—I thought I’d make the most of such lasting sentiments by working them into a review.

Augustus portrays the mostly-historical tale of a young man enamored with poetry and scholarship, who takes up arms and his legendary uncle’s name in a Republic embroiled in stasis, a country he unites with a small handful of capable, trustworthy friends—a group which, for the most part, survives the wars and is crucial in forming the empire Rome eventually becomes.

Williams weaves his oblique biography starting from the end of the Republic, a little before Caesar’s assassination, and ends it at the first imperial transition of power to Tiberius. The period’s main events are recounted through the correspondences of Augustus’ nearest and dearest: notable names include Agrippa, his chief general, and Maecenas, his culture minister; the most recurring entries in the novel are those from the journal of his daughter Julia. We meet Augustus himself only at the end of the book, in his old age, when he writes a retrospective to a historian friend which, as it were, functions as his informal address to posterity.

But since we don’t hear from Augustus throughout the book, and instead mostly about him, our perception of his character is strangely skewed. Until the very end, the first Roman emperor is curiously devoid of an inner life, even as many of his friends and family are shown to have exceedingly rich ones. We the readers are witness to Augustus’ public deeds and decisions, and some of their human consequences—which say a lot, of course—but they tell us little about the man we couldn’t have gleaned from a lyrically written work of history. Which leads us, as readers, to naturally ask: why keep the titular character so distant?

Williams’ professed aim is to probe a kind of inner conflict often faced by those in power—in his words, the tension between “the public necessity and the private want or need.” Perhaps for no other role is this tension more apparent than for an autocrat like Augustus, for whom all the powers of state have become concentrated in his person.

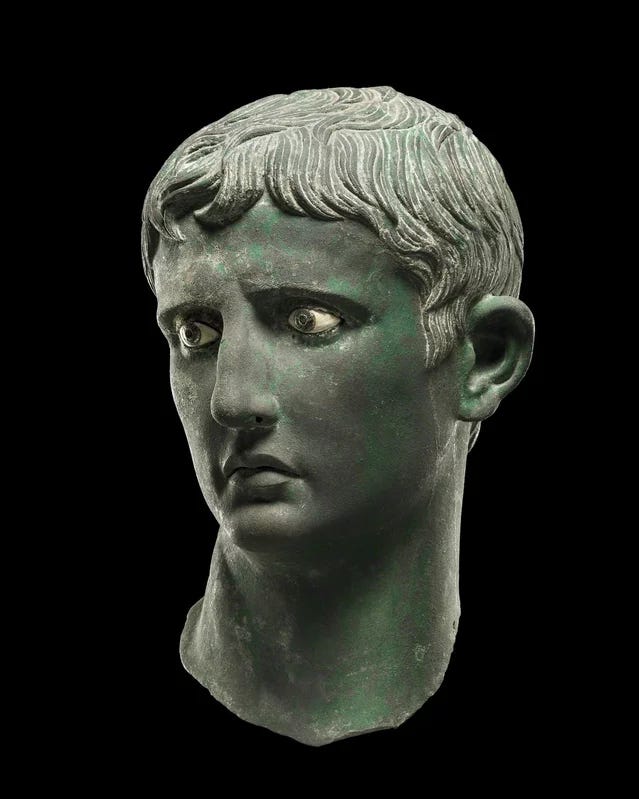

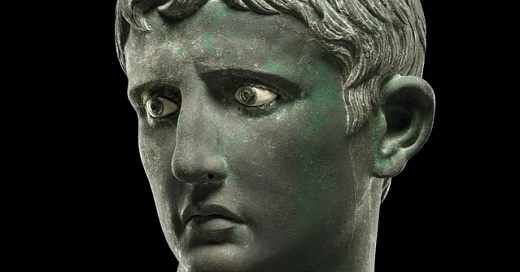

Viewed in these lights, Augustus’ remoteness for most of the book can perhaps be explained by his very real distance from the nation, who only ever saw his statues, heard his declarations, or used coins bearing his face; his imperial aloofness was also felt by many who were physically closer, who found they’d lost much of their former access to a family member. And no less are we made to feel this distance, if only in the piecemeal narrative flow of the story.

It’s difficult to say if there are spoilers, since much of what’s raised in the book reflects real events. Williams does his research. But the joy of the story, as is often the case, consists in the telling, and his drawing-up of the inner worlds of people responsible for the battles at Phillippi and Actium, the writing of the Aeneid, and more, is absolutely essential for anyone interested in the early Roman Empire (not to mention the contemporary literary scene: there’s some wonderful letters “written” by Virgil, Horace, and Ovid).

As it happens, I think the book is interesting also for psychological reasons. These will be the focus of this review. On the one hand we have Augustus, who tries to maintain constancy of character against the chaos of civil war and the dilemmas inherent to lonely rule. On the other hand, through a relatively more fragmented narrative, we get to see another character—Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony)—molded for control by external forces. Antony doesn’t appear very often in the book, but given his pronounced opposition to Augustus, he offers an easy, but I think ultimately fruitful, contrast to the latter’s character.

***

I. Ambition, risk, and the safe affection of parents. Stabilizing a sensitive soul.

Before he became Augustus (a title meaning “the majestic”), he was Octavian, scion of an old equestrian family. As a teenager Octavian spent time traveling with the military camp of his great-uncle, Julius Caesar, on their various campaigns. Having no sons of his own and impressed with the young Octavian, Caesar decides to name him his heir.

When the dictator perpetuo is famously assassinated, Octavian is undergoing military training in a Roman province far from the intrigues of the capital. Williams imagines a gap of time just before the 18-year-old Octavian accepts his inheritance—between “stimulus and response”, so to speak—when he receives word about Caesar’s death and his place in the will but hasn’t yet decided what to do.

At this time, the tyrant-killing Republican forces are attempting to rally their armies and reinstate the Senate. If Octavian accepts his proffered inheritance, he gains…a lot of enemies.

Sent in this decisive period is a letter from Octavian’s parents, who urge caution and withdrawal:

“Whatever his virtues, your uncle left Rome in a state from which it is not likely soon to recover. All is in doubt: his enemies are powerful but confused in their resolve, and his friends are corrupt and to be trusted by no one. If you accept the name and the inheritance, you will be abandoned by those who matter; you will have a name that is an empty honor, and a fortune that you do not need; and you will be alone.

Come to us at Puteoli. Do not involve yourself in issues whose resolution cannot improve your interest. Keep yourself aloof from all. You will be safe in our affections.”

—Letter: Attia and Marcius Philippus to Octavius (April, 44 B.C.); from Augustus

It’s worth keeping in mind that though Octavian has seen a thing or two with Caesar’s armies, he doesn’t really fit the picture of a warrior. Octavian as a teenager was a rather dainty-looking fellow, more interested in literature than legions. His parents’ letter therefore comes across in maybe two senses: (i), they want their child, as all parents do, to be free from harm, which he’d be abundantly exposed to if he accepted Caesar’s inheritance and/or (ii), their kid was so fragile that their concerns didn’t directly result from national circumstances, but were merely heightened by them.

So there’s a key thing Williams needs to show: how is it that mild-mannered young Octavian comes to rule the western world?

True to the form of the book, we learn how from an elder Augustus, who relates the following (and it’s pure Williams):

“It was more nearly an instinct than knowledge, however, that made me understand that if it is one's destiny to change the world, it is his necessity first to change himself. If he is to obey his destiny, he must find or invent within himself some hard and secret part that is indifferent to himself, to others, and even to the world that he is destined to remake, not to his own desire, but to a nature that he will discover in the process of remaking.”

—Letter: Octavius Caesar to Nicolaus of Damascus (AD 14), August 9; (bolds mine); from Augustus

What young Octavian seems to realizes about himself is that to change the world, he needs to develop a core of indifference—not because it’s a general virtue, but, I think, to compensate for a sensitive nature.

To react with strong emotion to clever turns of phrase is the virtue of a poet, not of a political and military leader. A key virtue of such a leader is instead ataraxia, often translated “imperturbability.” This is what Octavian realizes: since in many respects sensitivity is the enemy of expedience, he resolves to submit his developing self to the singular and supreme role of an autocrat, a position requiring him to treat great matters with a light touch—as opposed to, perhaps, that special poetic quality of adding significance to the small.

Augustus notes that this inner core, though indifferent to all, still respects his desire. And even if we don’t know exactly what this desire sought, we know from his behavior as ruler that little mattered more to Augustus than for his public image to appear virtuous.

On the virtue of this public image, he believed, rested the virtue of the new state he was building. After all, the images of several of Rome’s previous leaders were stained by corruption, even that of Augustus’ adopted and deified father. From Sulla to Caesar, recent Roman leaders had seized power that wasn’t theirs to take, or held onto power that wasn’t theirs to keep, sometimes both. This is why, even as the Republic and its ideals crumbled, Augustus hesitated to call himself emperor despite being so in all but name, preferring instead the title of princeps.

Maybe this sort of careful image is just what Rome needed after a century of civil war—an image of a leader with good ole’ Roman values, who honored family and hearth. But of course, when power isn’t shared, one is easily exposed to the charge of good ole’ self-aggrandizement. Augustus was pretty clever at blurring the line.

It’s also worth noting, in passing, that Augustus’ passage about his “hard and secret part” was penned as an old man looking back after years of war, the loss of several heirs, and after his banishment of his one and beloved daughter; looking back, perhaps he found the germ of his then-developed callousness in the moment when he first reached for his destiny. He winds up seizing it, of course. But at what cost?

“Socrates saw his friend, who was rushing to artists to order his image be carved upon rock, and he said to him, you are rushing for a stone to become like yourself, why not take care that you do not become like a stone?”

—Laurus, Eugene Vodolazkin

II. Why Antony betrayed Rome. Expert gaslighters and their subtly overpowering interpretations.

“IV. To protect the gullible and ignorant and poor, and to halt the spread of alien superstition, all astrologers and Eastern soothsayers and magicians are forbidden within the city walls, and those who now practice their vicious trades are ordered to quit the city of Rome, upon pain of death and forfeiture of all monies and properties.”

—Consul Marcus Agrippa, Senatorial Proceedings (33 BC); from Augustus

During times of social upheaval, unlicensed astrologers and other shady members of the spiritual economy would sometimes be expelled from Rome. The city’s native priesthood didn’t take kindly to those who usurped its religious authority; they alone professionally and legitimately divined the flights of birds and read messages in entrails.

The occasion for this particular upheaval was Antony’s repudiation of his responsibility as a Roman triumvir. During his extended dally with Cleopatra in Egypt, Romans began to think (nudged by Augustus, whose sister was Antony’s legal wife) that Antony was bewitched by the foreign queen. If such dark powers could take even the mind of one of Rome’s best sons, how much more susceptible would the average citizen be?

Even though he’s often depicted, along with Cleopatra, in a state of glamorous decline, Antony didn’t start out a degenerate. He was Caesar’s capable second-in-command, known for his courage in battle; a true soldier’s soldier. It’s only due to his lack of political acumen that he doesn’t take Caesar’s role after the assassination, and is instead forced to make way for the more politically savvy Octavian. Still, it’s also because of Antony’s seniority that in the uneasy alliance between the two, Antony receives the much better carving of Roman territory—he gets to govern the rich East, of which Egypt was the shining jewel, while Octavian rules rowdy Rome and the rebellious Northern provinces.

Williams presents Antony’s fall from civic grace as a gradual affair, suggesting it may have been delicately engineered for Egyptian political gain (as much as it may have been for love of Cleopatra). Antony’s mind turns into the site of a battle he finds himself unaccustomed and ill-equipped to fight.

Antony has become excessively reliant on an Egyptian soothsayer, a dependence he defends in a letter to Octavian by citing the credentials of the “High Priest of Heliopolis, the Incarnation of Thoth, and the Keeper of the Book of Magic” who acts as his advisor. When Antony has a disturbing dream, he presents it to this priest for examination, who then reports his findings and advice in covert letters to Cleopatra:

“He has had a dream of being bound to a couch while his tent burned around him. The soldiers of his army walked past the burning tent, and did not heed his calls, as if they did not hear him. Finally he burst his bonds, but the fire was around him so fiercely that he could not see which way to turn to escape. He awoke in fear, and called for me.

I fasted for three days, and gave him the portents of the dream. I told him that the fire was the intrigue in Rome, heaped and kindled by Octavius Caesar. That he was in a tent, I said, revealed two things: his position (he has no secure and permanent place in the Roman world), and his nature (that he is a soldier). That he was bound to his couch, I said, signified that by his inactivity he had betrayed his nature and allowed himself to become weak and hence impotent to the intrigues against him and to the circumstance of fate. That his soldiers did not heed his calls revealed that by his betrayal of his nature, he had lost control of his men; that he is properly a man of action, not of words; that men would bend to his deeds, not his talk.

He has become thoughtful, and he studies maps. I say nothing to him, but I believe he is again considering taking up arms against the Parthians. For this, he will come to know that he needs your aid. Discreetly, let him know that it is at his disposal. Thus, you may draw him again to our cause, and insure the future glory of Egypt.”

—Extracts from Reports: Epimachos, High Priest of Heliopolis, to Cleopatra, the Incarnate Isis and Queen of the Worlds of Egypt (40-37 B.C.); from Augustus

There’s a number of things here on which we can hang our analysis. But the most protruding phrase is no doubt “betrayal of his nature.” Perhaps no other injunction would be as provocative in inciting Antony to action, as it suggests both a deep familiarity with what Antony actually is, deep down, while offering a way for how he might become “more himself.”

Now, people seek spiritual guidance for any number of reasons. It’s hard to predict when this sort of need will arise, and for whom, in advance. But I notice it’s often the case, anecdotally speaking, that this sort of seeking is done when attempts at sculpting or discovering one’s own character have proved fruitless, a vulnerable period when we seek out such stable influences as those who make a living from guiding vulnerable souls to some inner reconciliation (priests, therapists, or astrologers, take your pick). And it’s often doubly surprising when the people you see in this vulnerable state are those whom you thought were particularly stalwart souls (soldiers being exemplars of toughness, etc.).

But Williams’ portrayal of Mark Antony as one of these vulnerable people is interesting for yet another reason which contrasts with Octavian. The real Augustus makes himself—and after him all Roman emperors—into the pontifex maximus, the traditional high priest of Roman religion.1 That Augustus turns into a spiritual authority while Antony becomes a spiritual subject, I think, suggests something important about their respective characters (or rather, something important about Williams’ depiction).

***

The classical world tended to think about character differently than we do. We may think it’s the most fitting mark of being conscious, rational creatures that we express our inner feelings and conflicts; but according to certain ancients, that our actions take place within stories is what really distinguishes human life.2 This is partly why Aristotle and many of his interpreters, working in the domain of what’s now called “virtue ethics”, rely so heavily on theater and biography to illustrate character.

Much is made of character development in storytelling, usually described in the form of a person acquiring new, previously unpossessed virtues, or through the refinement of those he already possesses. But what virtue, if any, keeps a character reliably them?

Philosophers through the ages have offered tables of virtues that differ substantially from one another but with some commonalities—courage, temperance, and wisdom, for example, are often featured. People might possess some or all of these virtues to different degrees, forming variable (but stable) combinations we might imagine make up unique characters.

But one modern interpreter of virtue ethics, Alisdair MacIntyre, is inclined towards an idea of Jane Austen’s which places constancy as the central virtue, perhaps even the prerequisite virtue for all the others.3 And it’s possible that what appears as “indifference” for young Octavian we might just as well call constancy, or maybe, the “intention-toward-constancy.”

Constancy unites and reinforces our actions across time, linking what we’ve done or promised in the past with what we do or owe today, and likewise, into the future. It’s a commitment against all “threats to the integrity of personality” that exist in the world, as MacIntyre puts it.

And I think this virtue might offer a way to understand a key difference between Antony and Octavian (as Williams portrays them). After he accepts the name of Caesar, Octavian has decided that his destiny calls him to save Rome. He puts his role as “pater patriae” over being “pater” to his own daughter when she violates his laws. In the clash between public necessity and the private want or need, for Augustus, public necessity won—he’d decided before circumstances changed that a deep-seated part of him wouldn’t change with circumstances. And as a result, the force of Octavian’s character invention flowed out from him into the world, and became a rectifying—if authoritarian—influence on his warring society.

In contrast to Octavian, Antony might instead be understood as the person who chose love over his public image, who preferred the present over posterity. Antony went against his role as triumvir, or even Caesar’s former second, and accepted a definition of his identity from a person who didn’t share his history, and who had interests distinct from Antony’s welfare. In accordance with Williams’ central tension, Antony losing his personal identity came with losing the political “big picture” as well. Now we remember him more as a doomed lover than for his political ambitions.

I’ve emphasized the invention of character more than its discovery here because there’s no dearth of signals out there telling us to “go and find ourselves”. We’re often told that we can learn more about ourselves through our reactions to a diverse range of experiences. This view isn’t entirely wrong, of course, but it’s starting to seem, to me, quite incomplete. I think we underrate how much the strong intention to form a stable self can power us through different environments and varying needs, keeping us, deep down, the same person. And to some extent, this intention is probably required for us in the present to feel continuous with our pasts.

That the self-story we tell ourselves could be otherwise isn’t reason to dismiss the telling; the point was always about control, not truth. Perhaps we can only hope the truth of our natures emerges with time, as it did for Williams’ Augustus, despite his prodigious strength for self-invention.

This is perhaps the longest running position of authority in Western culture, as it began during the Roman monarchy under King Numa (~700 BC) and has survived until today through the Catholic papacy, which still goes by that title.

For Aristotle, character supervenes upon or emerges from the sum of actions a person makes, a floating picture from which you can get a sense of their inner dispositions. (In some ways, Aristotle’s views on character are not unrelated to his ideas on action and narrative raised in the Poetics.)

What character is not, classically speaking, is dependent on mental valences—whether we make ourselves or others feel good or bad—as today’s utilitarian viewpoint would suggest.

Discussed at length in After Virtue by Alisdair Macintyre.

I had absolutely no idea Jane Austen comes up in After Virtue. You might have given me the final push I needed to actually pick it up!

Great review.