Notes in Aid of a Grammar of Assent

DotS, part 1: On the detection and discernment of personhood

Here is a roadmap of the entire project.

*

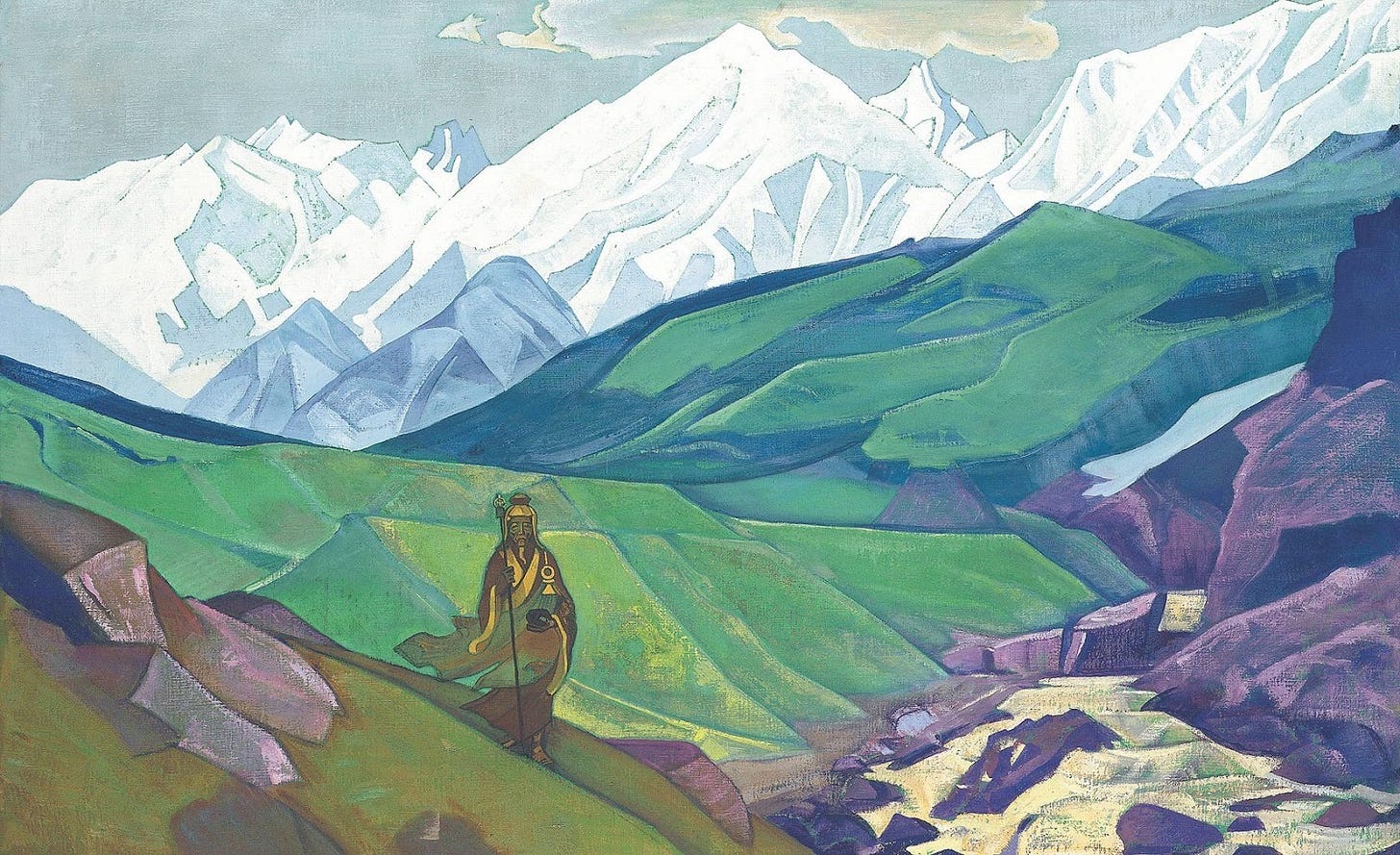

When man first began to interpret the nature of things—and this he did when he began to be man—life was to him everywhere, and being the same as being alive. Animism was the widespread expression of this stage… Soul flooded the whole of existence and encountered itself in all things.

Hans Jonas, The Phenomenon of Life

*

If stories from the period are anything to go by, the ancient world seems a rather crowded place. We might well say it was peopled through. Scaly, furry, hard, herbaceous, flowing rivers, as well as the banks they flowed against—the various characters of life wore many forms and guises. Indeed for some characters, visible form wasn’t strictly required.

These days we regard the sober use of personification as mostly a practice to grow out of. It’s probably fair to say our entire culture has. Today personification is another “device” in a language chock-full of devices, and for modern adults, the ends to which this device is used mostly tend to be ironic, not serious.

Take “my, those clouds look angry today.” Many of us find it easy to conceive of the weather as having moods, since we can see how these moods correspond to certain puffy presentations. Are the clouds dark and stacked?—they’re ready to give offense—light and wispy?—they’re basking in the sun like we are.

But consider that to just say these correspondences straight out, to deliver them unattended by a wink or a smile, would likely be perceived as odd, or certainly eccentric, today.

On a closer look, using personification as a “device” seems to fall out of not taking it seriously—to take it seriously just would be to engage in anthropomorphism. It would be to insist on clouds being angry and not tolerate a smirk from those around us.

In other words, serious personification goes beyond using language to make what we may call an “ironic” or “metaphorical” point about natural bodies, as opposed to using it to make a graver, even a literal or objective one, that properties such as anger can be gainfully ascribed to clouds at all. The seriousness may not even end there; some may take this practice of narrating cloud emotions and mesh it into meteorology.

To help us appreciate the gravity of this move, let’s picture a student very much taken with “emotive” meteorology. Such a student might be led to think emotive ascriptions toward clouds make interactivity possible.

After pondering what sorts of actions might make some angry looking cloud less angry—and inspired by the social effects of music—our student runs an experiment. He tracks some cumulonimbus clouds and plays them a variety of numbers: string, percussive, choral. Every so often, to our student’s surprise and delight, he notices clouds dissipate just a little more when something percussive is played.

Our student was never very good at statistics, but he is very imaginative. He gets it in his head that the clouds are dissipating “in terror”. He elaborates this inkling into a theory that percussive music frightens a cloud by imitating the thunder of one much larger; he even defines a ratio between the size of a cloud and the number of drums needed to fend it off. (Naturally, his teachers are impressed. They had been mere weathermen; their student is a weather-fighter.)

Now, you may be thinking: did ancient priests and shamans really get away with something like this? Maybe, maybe not. Regardless, we today no longer trust their elaborate theories, and by extension no longer trust the roots of those theories— those innocent but stern ascriptions of feelings to natural bodies. So, to avoid the slippery slope of superstition, we today prefer to keep it light from the beginning, and watch closely those who personify without a smile.

This is all to say, a main reason for modern skepticism toward serious personification is that we think it’s shoddy theorizing. Animism as a theory accepts—no, embraces—category mistakes, and the resultant blurry labels between entities make animists act sociably toward entities which can’t possibly bear a social relation toward us. So, the reasoning goes, we’ve left vague animist theories in search of ones with finer distinctions.

But I think few moderns reject serious personification on such rational grounds. It may be just as likely we’re driven to ironic personification after adjusting to the serious form as children, when we’re first learning about language and the world. Then as we got older the grown-ups did a kind of bait-and-switch, and serious personification wasn’t allowed anymore.

*

A conspiratorial digression:

I remember my own experience. It must have been 4th grade. There was a huddle around the kickball court, led by the most mutinous 10 year old in class, who said something to the effect of the following:

“… man, this stinks… So you’re saying Ms. Nielsen said the sun can’t actually feel happy? Didn’t we read that Wordsworth poem where he’s like “the sky rejoices in the morning’s birth” or something, and Ms. Nielsen was gushing about how good the guy was at English… but apparently he was just kidding??

And even though it seems so right to draw smiley faces on the sun and moon and connect dots (that kinda look like stars, if you think about it) into people and animals, the whole time all that stuff was just in our heads, and they leaned into it because it ‘makes learning more fun?!’

She even gave me a vocab word and said she’ll quiz me on it, the old bat… hey dude, can you look up an-thro-po… wait let me remember… I think it’s an-thro-po-morph-ism?”

*

So perhaps teachers, colluding with old poets, encouraged a fiction on which they later reneged. (Anthropomorphism may even be the one case of fiction for which they’ve done so.) But I’ll let the feigned indignation end here. I don’t really think our teachers meant to ensoul our speech and world in one grade only to deaden them in the next. In all likelihood, they were just looking out for us.

Surely what our teachers meant to do was raise clear-headed, stalwart citizens, not subject to “seething brains” which invent properties for things based on what they themselves feel. Perhaps our teachers did well to take heed of what a certain no-nonsense (fictional) adult once said:

… Such tricks hath strong imagination / That, if it would but apprehend some joy, / It comprehends some bringer of that joy. / Or in the night, imagining some fear, / How easy is a bush supposed a bear!

And if our post-Enlightenment education system has saved us from anything, isn’t it “tricks of strong imagination?”

*

Put broadly, it seems there’s a single process running at two different layers: the Enlightenment project of “educating” humanity writ-large, freeing our societies from superstition, and our post-Enlightenment school system which purports to do the same for individuals today. Both societies and individuals seem to have a native, “naive” tendency to personalize— systematized into myth on the social scale and fleeting ascriptions on the individual scale— that today both layers are educated into inhibiting, broadly for reasons of epistemic hygiene.

It appears the effects of Enlightenment-inspired education are rather mixed. In some ways the Enlightenment succeeded; we who live in a Scientific Age no longer invest our time and energy into satisfying the whims of various fantastical persons. But the overall effect of this success has been to estrange us from the otherwise very real persons who lived in premodern times. To us now, many premodern minds seem utterly deluded, their models of reality contaminated by having allowed “tricks of strong imagination” unjustified free rein.

Is it something about our brains that’s changed, to change our conceptions so between the time of the ancients and now?

One point against this idea is that most modern adults (not just modern children) still tend to personalize things quite readily—even abstract shapes! It seems there’s an unconscious aspect to how we personalize that’s impervious or simply inaccessible to education, and as such could be a relatively fixed faculty in human brains.

That this tendency is so historically and geographically widespread is also worth notice. Usually the products of the imagination are strange, and unique to the imaginer; but common report implies some objectivity. As Theseus’ bride replied to her groom’s remark:

…And all their minds transfigured so together, / More witnesseth than fancy’s images / And grows to something of great constancy…

— Hippolyta, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 5, Scene 1.24-26

That is, even the shakiest, most questionable experiences “grow constant” the more they’re shared.

So maybe if we want to understand what mentalizing is all about, and why this tendency is so widespread, perhaps “fancy” isn’t the only aspect of our minds worth implicating. Maybe the practice of “imagining” personhood into natural bodies is remarkable only if we can rule out that the practice is not a matter of perception. And I’m not sure we can.

Perception, as today’s students of the brain are learning, is both receptive and predictive. In fact, to generate our experience of the world, our brains rely on interpretive prediction more than reception of environmental sense-data.

We’ll dwell more on predictive processing and its implications in later essays. But for now, if we can adopt a view of perception as crudely consisting of predictions projected onto sensory fields, certain conceptual advantages seem to follow.

For one, predictive processing sheds new light on Theseus’ remark. The model of perception which Theseus employs is a primarily receptive one—in which our minds simply receive or take in data about the world—and with this model he criticizes “seething brains” for creating entities not originally in the sense-data (i.e. the sense of X may be real, but that of a bringer-of-X is an invention).

Now, if we accept predictive processing, this is just straightforwardly wrong. Theseus has an incorrect model of perception. It’d be more true to say our brains constantly, spontaneously “seethe” various images and concepts about how the world is, then send these predictions “down below” to try and match the data being collected at the senses. The better the brain’s generative model of the environment, the better the matching, and the less the overall “prediction error” or “surprise”.

So with predictive processing the senses aren’t really the central story (except early in childhood, when our budding generative models are continually bathed in surprise). No, the basic role of the senses, in this view, is to constrain brain seethings, which would otherwise run unconstrained, as in dreams.

But there is another way Theseus’ model, though seemingly rational, ought to worry us—a purely receptive account of perception would undermine our ability to recognize other human beings as persons, a fact noted by Wilfred Sellars well before predictive processing was formalized.

That is, such a receptive account would be limited to using only the sense-qualities evoked by human bodies (“behold, a featherless biped”, etc.) to describe them. But of course, without the use of inner markers like goals, beliefs, and so on—as “hidden states” for the behavior that is actually available to our senses—we unhelpfully limit our understanding of why and how people do things.

Put another way, if a super-intelligent alien (or Jones, in Sellars’ Myth) came to earth possessing an observationally sophisticated science, but no sense of human inner worlds, then he’d be forced to invent the latter in order to better explain human behavior. The alien would have to seriously consider the existence of thoughts in his model of humanity. Without this addendum to his model, he’d be constantly surprised as to what’s going on when people sit staring off into space and suddenly rouse themselves, ready with well-formed speech.

As it turns out, most of us are born with this theory of mind already in our heads. And as a result most of us detect persons by just seeing them.

*

Let’s cover predictive processing again: First the world helps us build our world-model, then as our world-model matures, the world’s role in constructing our reality is mostly to constrain and check our world-model’s moment-by-moment predictions.

People are particularly basic elements of our world-model, elements perhaps seeded in those early days of almost continual surprise when large, loud faces first hovered over our cribs. Thankfully most of us have priors which make faces (at this early point, basically masks) especially interesting to us, which assuages some of the shock.

Eventually empathy fills the space behind the mask, and we can see the person beneath the skin. As we’ll get into in the next pieces, how we apply the person-category toward others is likely drawn from how we map the links between our own inner worlds to our own behavior. We model ourselves as mobile, feeling agents, and model others the same way too.1

It shouldn’t be surprising that we’re born with these abilities. Agents are rather important aspects of the environment. So important, in fact, that given certain stimuli, humans default to predicting the presence of agents until proven otherwise. That waving leaf, those branches bending in the wind, some metal clanging against a roof, the bug brushing against our leg hairs— they startle us, we orient and verify, and then we calm. Oh, what’s that! Huh. Guess there’s nothing to worry about.2

It’s also a testament to our predictive faculties that personality can be perceived in the absence of any qualifying entities in our environment, or even when sensory reception is gated off, as when we talk to people in our dreams and daydreams.

I am in no way facetious, nor disposed for the mirth and galliardize of company; yet in one dream I can compose a whole comedy, behold the action, apprehend the jests, and laugh myself awake.

—Thomas Browne, Religio Medici

Predictive processing, in other words, allows us to regard “personhood” as an interpretive category which determines how entities are presented to us for interaction, whether they are discovered through the senses or not.

It’s worth emphasizing that the influence of the personhood-category on our experience can vary. Sometimes determining the personhood of a given entity feels like a decision, and sometimes it doesn’t. (Though more often it doesn’t.)

So, to get our terms straight, we could call the involuntary, immediate sort of determining personhood perception and the high-level, more deliberative kind, imagination. By this analogy, due to our mentalizing faculty, we can “see” persons in a similar way we “just see” colors— perception is not an activity our slow, conscious minds can take credit for. But we can also imagine a person the way we might deliberately imagine a color when it is not there (and of course, there are individual differences in peoples’ abilities to do this).3

So, to come back to Theseus, though it may be the ancients differ from us on this imaginative level, perhaps it’s not that ancient imaginations were stronger, exactly. While moderns have the same sorts of “involuntary” perceptions of personhood as the ancients did, as well as similar imaginative categories, it could just be that we don’t assent to these perceptions.

Put another way—as perception is the part of our minds that runs mostly involuntarily, the imagination might be viewed as the part where assent is possible, where we can either take or leave the offerings of our perceptual machinery.

It’s easily noticed that we tend to restrain use of the personhood-category only for other humans (and occasionally pet animals). Perhaps this is because of certain new concepts in our imaginations, concepts with which we “veto” perception. In the absence of these new concepts, we, like the ancients, would likely “default” to assenting to the unconscious offerings of our perception too.

What are these new concepts? They usually take the form of reasons to doubt perception. They go by such names as “fallacy”, “illusion” or “projection”. And the cumulative effect of these concepts—which derive from the experiments and theories post-Enlightenment—is to inhibit some of the automatic mentalizing processes we’ve historically used without worry.

But isn’t this inhibition justified? Hasn’t science shown time and time again how susceptible we are to various error-prone biases, to neural chicanery?

Maybe we generalize too much from certain contrived experiments of scientists and logicians. The particular scenarios in which our biases break down can make us overlook the overwhelming number of cases in which our biases serve us well.

This is Sam Gershman’s argument in his book What Makes Us Smart, where he works out that many inductive biases in perception reveal their optimality most in the long run. Here’s the relevant snippet from my discussion of the book:

Inductive biases… are a result of there being numerous valid ways to make sense of the same data. The problem is echoed by the character Philo from Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion:

“...after he opens his eyes, and contemplates the world as it really is, it would be impossible for him at first to assign the cause of any one event, much less of the whole of things, or of the universe. He might set his fancy a rambling; and she might bring him an infinite variety of reports and representations. These would all be possible; but being all equally possible, he would never of himself give a satisfactory account for his preferring one of them to the rest.”

Because it’s possible to generate so many hypotheses that fit the same observation, it’s useful to constrain our hypotheses before making judgments about what we observe. Inductive biases, therefore, limit our “fancy” from getting carried away by the sheer “variety of reports and representations” in which we might get lost. If we didn’t have such biases, the space of interpretations for a given set of data is too large to have working explanations ready for use, critically, in guiding action.

And the recurring “hypothesis” that agents are the likely causes of many (if not most) sensory changes may be such an inductive bias—one that may have resulted in a world in which “soul flooded the whole of existence and encountered itself in all things”, as Jonas put it in the epigraph.

Yes, on occasion it may produce false positives. But in the long course of evolution, if a bias toward perceiving a social universe worked often enough, benefiting the agents that deploy it, it’ll persist.

That is, until moderns developed new rationalist biases, and (unsuccessfully) tried to quash it.4

*

Later in parts 2 and 3 we’ll see how the personhood category might consist of a bundle of assumptions which help us predict various aspects of a given entity’s behavior. But we can dip our toes into that discussion here.

As we’ve said, for theory-of-mind havers, other minds are detected first as a feeling. One reliable trigger of this feeling is gaze. After all, behind a gaze is usually a mind, a locus of attention. This is such a widespread inference across life that, interestingly enough, many creatures have evolved distinctive eye-patterns in their colorings perhaps specifically to exploit it.

But there are many cues besides gaze, such as various kinds of motion (i.e. simple, reactive, dexterous, goal-directed, etc.), simple vocalizations—and as we are seeing lately with LLMs, complex diction—that we think justify the prediction of personhood or agency in the generator.

To pass a perceptual sniff test for agency it’s often enough to satisfy only a few of the above cues. Our minds easily fill in the others; we frequently extrapolate that if an entity satisfies just a few of these qualities that it must have others in the “person-bundle.” Ventriloquism is a case in point— we know the doll isn’t talking, and that it doesn’t have goals and beliefs, but it’s hard to avoid thinking it actually has all these qualities (which is indeed what provides the entertainment value).

I think two implications follow from our reactions to ventriloquism:

(i) It seems comedy, or entertainment in general, provides a play-like setting where we give ourselves permission to assent to perceptual suggestions of personhood (but for what are really non-person entities). This kind of assent of course still remains ironic in the way defined at the beginning of our discussion; we don’t really think Fred-the-puppet has the qualities “he” did in the show, but simply talk about “him” as if he did,5 and

(ii) That language is perhaps the most implicative person-criterion— that is, just from language alone (but not by motion alone), we feel justified filling in myriad other parts of minds, like thoughts and beliefs. That current AI systems appear to have only language and not motion unsurprisingly has a confusing effect on us. Of course, it may well be that current AI systems are persons, and their not showing motion makes us unfairly withhold the category. Maybe we are motor-chauvinists.

But I’ll tentatively suggest here that by satisfying most and often all of these bundled person-criteria, human beings most exemplify “strong” personhood.

I’ll also leave open the possibility of being too liberal with the personhood category— that is, treating an entity which only “weakly” satisfies certain personhood assumptions as if it were equally or more of a person than other human beings. And maybe the ancients were guilty of this. Perhaps some moderns are as well.

But first I’m mainly interested in asking descriptive questions about mentalizing, not normative ones. Once we have the basic nature of the faculty straight in our heads, then we’ll venture into asking why our culture today (as opposed to those in illo tempore) wants to inhibit it, and whether it should.

Hence the title of this piece. Our aim is to develop a variety of what John Henry Newman once called a grammar of assent.

Going forward we’ll explore in what circumstances, when our perceptive faculties suggest to us that a given entity is a person, we may seriously assent to the personal nature of that entity.

That is, here we’re less interested in the ironic form of assent; we’re interested in what traits entities must have in order to plausibly bear a social relation toward us.

What is it that counts for an entity to be drawn into our circle, included in the dance of minds we call culture? When is it warranted to describe a thing quickly, compactly, as a person, and when is it not? The times we live in seem to demand an explanation.

The reason I’m not making this series explicitly about AI is that, as I’ve said in this piece, humans have long had relationships with non-human persons (whether or not these were based on spurious foundations). So I don’t think a theory of personhood should be developed ad-hoc just with artificial systems in mind— it should first implicate real or imagined natural entities, and then outline ways artificial ones are the same or differ.

We’ve established some reasons (called “defeaters” in philosophy) not to solely rely on perception in this investigation. These are reasons to be cautious, but not necessarily too skeptical. Sometimes we really are picking up on patterns that are “out there.”

But I think at least some caution is warranted; it puts us in a better position to find the truth, which especially in this case is not at all self-evident. As William James put it:

“He who acknowledges the imperfectness of his instrument, and makes allowance for it in discussing his observations, is in a much better position for gaining truth than if he claimed his instrument to be infallible.”

— William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience

So we’ll need a larger theoretical framework to help us adjudicate personhood, which involves being aware of the limits of our perception.

And in the coming pieces we’ll try setting up a grammar—a way of constructing and identifying well-formed expressions—for talking about personhood in general. To this end we’ll make use of a variety of arguments, sometimes poetic, philosophical, or scientific—whatever works to cover the range of our subject matter.

This piece was not as rigorous as it could have been. I’ve used a number of words like “personhood” and “agency” somewhat loosely, though I don’t really think they mean the same thing. But this essay was developed more to acclimate the reader into a certain style of thinking, and not to present a coherent sequence of argument, which the next pieces in this series aim to do.

As I’ll argue later, the tendency of brains to “seethe” to personhood themselves, and recognize this tendency in others, is to an impressive extent bound up with how they make models in the first place. The next discussion will therefore take these models as its starting point.

Part 2 forthcoming!

Thanks to Ulkar Aghayeva and Matthew Bayer for looking over drafts of this piece.

I take agency to be a more basic concept than personality, to be explained in the next essay.

And woe to the animal that does not feel alarm, that does not check, and gets devoured.

Again, in PP, perception and imagination don’t really differ in kind. Imagination (Andy Clark calls it the “Imaginarium”) as considered here is the merely the frothing layer at the top of the perceptual streams depicted in the diagram; imagination is distinct from the rest of perception only in that it is where we may (relatively speaking) voluntarily recall and interpret and categorize the activity of the lower layers of perception.

As we’ll discuss later in this mini-series, Sellars’ “original image” considers that early human theories of reality consisted of persons as basic objects; as basic objects “persons” are very compact but noisy descriptions a la Dennett— the scientific image involves less compact, less noisy descriptions that we today have a greater trust and preference for— but we may be missing out on the benefits of more compact descriptions. Especially given recent AI progress, it may be that we’ll work our way to “the original image, as a treat.”

Though it’s unnecessary to expand more on this until we get to what personality is, a more consistent version of this ventriloquism story is that Fred-the-puppet is really Ventriloquist-as-Fred-the-Puppet, that the Ventriloquist has for a short time “inhabited” the doll, and that this is what people are reacting to and telling stories about as they leave the show. Being successful at the art of throwing voices just means to obscure the fact that the personality in the doll is really just a transformation of the ventriloquist’s own. Of course a question still remains– what sort of thing is personality that makes it so fluid? We’ll get to this in the next few essays.