My favorite way of describing what makes sport special comes from a now classic DFW essay on Roger Federer and tennis:

The human beauty we’re talking about here is beauty of a particular type; it might be called kinetic beauty. Its power and appeal are universal. It has nothing to do with sex or cultural norms. What it seems to have to do with, really, is human beings’ reconciliation with the fact of having a body.”

Now, it’s not my intent in this piece to further describe that kinetic beauty, at least in poetic terms. If you find yourself hankering after such descriptions, one could hardly do better than DFW’s essay linked above, or Faulkner’s essay on horse-racing.

And neither do I intend to discuss “tribalism”, “simulations of war”, or any aspect of sport we might associate with base or primal aspects of human nature. No, it’s simply that kinetic beauty which fascinates me. How and why does excellent movement excite the heart so?

We’ll be going quite a-ways to figure this out: think Ancient Greek poets in conversation with physiologists, ancient meters sung aloud in the wing of a research clinic. Another day here at Sic Vita, in other words.

***

I. The Altar of Sport

It certainly appears, from the outside, as if sports enthusiasts make much ado about nothing. Their scrupulous record-keeping turns even the subtlest maneuvers into the stuff of history—each dive and dip is counted, points are argued over and logged, and every sign of graciousness or frustration is marked on an athlete’s character. And if the “little” acts are important, those who make them are even more so: star players can become saints, and jerseys become lucky or cursed for reasons beyond human understanding.

For the uninitiated, the context of an athletic achievement is often lacking. Thankfully, we aren’t left to interpret things ourselves; thankfully, we have commentators, our high priests of sport. As repositories of tradition, they act as “significance funnels” that direct our fitful attention to what matters on the field, their play-by-play analyses helping us make sense of athletic achievements we may otherwise, without them, miss entirely.

Now imagine a similar, but different job: what if the commentator was basically a propagandist for only the winning athletes? Don’t picture the impromptu praises of today’s ecstatic commentators; instead, imagine the skilled preparation of special verses for the victor, a grand poem in which the accomplishments of a successful athlete are grafted onto their culture’s mythology. This was the role of the “epinikian” poet of classical Greece, who sung “epi-nikos”—roughly, “about/on victory”.

Epinikian poetry emphasizes the figures of athletes, but not in the statistical sense. It mainly consists of geographical and cultural references weaved into a myth, with occasional mentions of competitors, and no—and I mean none at all—running times or splits. The job of these poets was simply to elevate the accomplishments of the winners.

Among the most famous of epinikian poets was Pindar, who lived and wrote around the time of the Persian Wars. He’s sometimes considered the greatest Greek poet after Homer.1 In contrast to Homer’s epics, however, Pindar is famed for his work commemorating the triumphs of winners at games then held regularly across Greece, which were dedicated to different gods: the Olympic games for Zeus, the Pythian games for Apollo, and so on.

A frequent theme of Pindar’s poems is that the striving for goals one earnestly desires is supremely attractive to the gods. Sensing such anomalous levels of human motivation, it was believed, moved the gods to move the desirer closer to their goal.

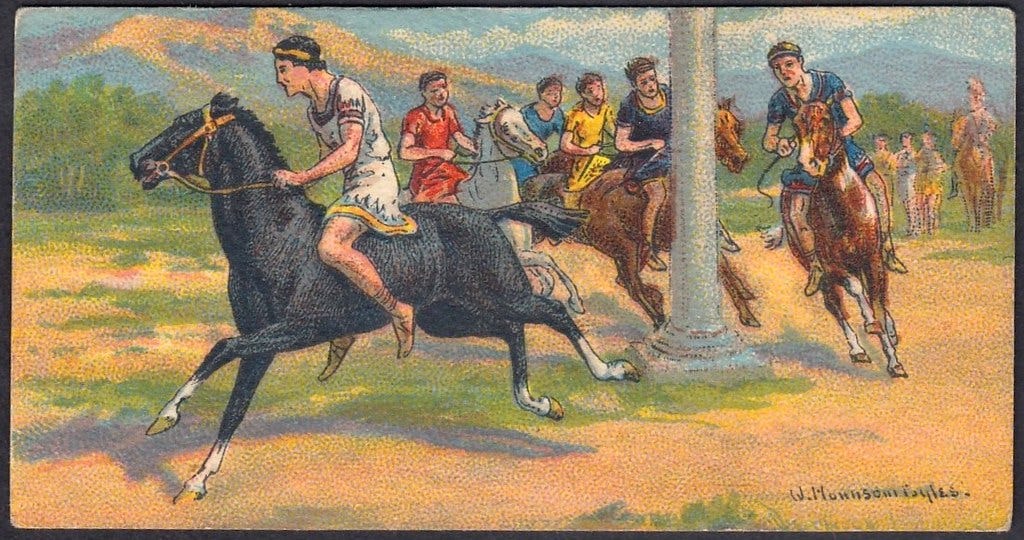

A prime example of this is found in Pindar’s ode to a man named Heiron, the victor of a single-horse race. In the first of the “Olympian Odes”, Heiron is compared to a mythical figure named Pelops. I’ve excerpted a section here:

“And about the time of his [Pelops’] handsome youthful bloom,

when downy hair began to cover his darkening jaw,

he turned his thoughts to an offer of marriage

that was offered to all: to win at Pisa

the famous Hippodameia from her father Oenomaus.Alone, at night, he went down to the grey sea’s shore

and called out to the deep-roaring Lord of the Trident;

and the god was there, close by him.Pelops said to him…

‘…Thirteen suitors has Oenomaus killed,

and in this way delays the marriage of his daughter,Cowards do not seek out great risks;

men must die, so why should anyone crouch in darkness,

aimlessly nursing an undistinguished old age, without a share in glorious deeds?

This contest is meant for me; now give me the success I desire.’So he spoke, and his pleas were not in vain.

The god gave him honor,

and a golden chariot with tireless winged horses.

So he defeated Oenomaus, and won the maiden to share his bed,

and fathered six sons, leaders of the people,

all of them thirsting to do great deeds.

And now he luxuriates in splendid blood-offerings

as he reclines beside the ford of Alpheus.

His tomb beside his altar is well tended,

thronged about by many a stranger……Some god, Hieron, watches over your ambitions, making them his concern…”2

—Olympian Ode 1, Pindar (bolds mine)

The story of Pelops showcases a mythical instance of how bold ambition can win lasting fame. It’s worth pointing out that his boldness carried him much further past winning the bridal competition—Pelops ends up fathering “leaders of the people” who possess some of his own striving character; even in death, people still dedicate sacrifices (blood offerings) to him, and thus keep his memory alive; further still, his tomb is flocked by strangers, much as the tombs of famous artists and thinkers are today.

All this because he demanded help from a god, instead of requesting it humbly, as others might. Pelops made it clear he was no charity case. And in this way the gods’ patronage seems little different from how the Medici supported the artists of their time: the gods are portrayed by Pindar almost as cosmic aristocrats—having accomplished the great task of setting the world in order, they watch a mortal in that precariously balanced world strive to achieve shadows of their own celebrated acts. And in their struggle and excellence, those fragile humans exhibit qualities exemplified by the gods themselves.

Sports commentary has indeed come a long way. Where today’s commentators announce records of facts and times, and compare live actions with lists of older achievements, the ancients recorded victory itself, and sung of how a victor entered the atmosphere of achievement which, for the Greeks, was inextricably linked to the divine.3

***

Though DFW said the appeal of sports is universal across cultures, there are of course differences in appreciation within a culture. Earlier I made a half-formed distinction between fans and the uninitiated. The former may find rich meaning in an athlete’s subtle movements while this significance is missed by the more casual appreciator. Here we find another natural analog to religion.

St. Augustine once commented that the church of his time was a “corpus permixtum”, a “mixed body” of believer and unbeliever sitting alongside one another. Never is this so apparent as during major holidays, like Easter, when the “culturally” religious and the truly religious partake of the ritual together. This of course resembles to a great degree the makeup of a Super Bowl audience, or an Olympic stadium, where people who rarely tune into sport do so out of cultural obligation and find themselves packed in with “fanatic” fans.

So how are we to understand the appeal of sport when the basis of its appreciation differs so drastically between audience members?

The classical practice may help here. Epinikian poetry was mainly directed not to sports fans purely interested in the stats, but to the demos, for people from all walks of life who came to watch the games. The poet’s role was to articulate a story by which sports excellence might translate to general excellence, and, using myths most people knew, to present an ideal of vigor—not just enumerate facts. This job of adding luster to laurels, quite understandably, had to be done by the best poet, themselves selected by contest.4 No one else would do.

The transformation from the unique example of excellence to the general is done relatively quietly in our own culture. It’s usually an exercise “left for the viewer”, so to speak, who takes whatever grit and passion athletes show and derive from it a mechanism for personal strength (e.g. “mamba mentality”). It’s interesting to imagine how our society might be affected if this transformation were to be made more explicit: if we could hold a space in our society alongside sport for a general picture of vigor that we collectively endorse. Or perhaps we do this already, and I’m just missing it?

II. Behind the Altar

“Arise, awake, and stop not till the goal is reached!”

—Swami Vivekananda

There’s two things about the allure of sport one might try to explain through other means besides poetry. The first is what immediately captivates—kinetic beauty, the successful use of smooth and forceful movement—while the second is the very source of an athlete’s vigor, what enables them to tirelessly pursue their goals over long time spans.

As every embodied being knows, complicated movements become smoother and more precise with practice. But unlike pottery, cooking, or similarly genteel crafts, sports, especially at the highest levels, demand precise movement while often requiring all the force an athlete can muster.

The trouble is, the more forceful you want a movement to be, it often comes at the expense of control. This is because activating a single muscle bears a certain amount of noise, which we might think of as the “gap” between intended and achieved motor output. But ultimately the amount of motor noise scales with the recruitment of more and larger muscle fibers, which needs to happen to increase the force of a movement (see Henneman’s size principle). This means that any sufficiently forceful movement in which many, large muscle fibers are used will tend to be extremely jerky.

Here’s a figure illustrating the downsides to “endpoint accuracy” when too many muscles are activated. The person in the figure intends the same endpoint with his finger each time he raises his arm, but he takes different paths between the two kinds of movement. In movement A, which appears smooth, he recruits only the necessary muscles for the motion. The “cloud” of possible endpoints for his finger is pretty small. But in more jerky movement B, more and larger muscles than necessary have been activated, and the resulting increase in motor noise results in a much larger cloud of possible endpoints.5

This will all likely be familiar to anyone who remembers their very first tennis serve or basketball free throw. During the first try, way too many muscles are used, not to mention the large muscles are used inefficiently. This typically results in wasteful, imprecise movement and a disastrous serve or free throw; a look under the hood would reveal a storm of noise in the nervous system.6 But over time, we prune away muscle-activations that don’t help us achieve our goal.

Reducing this kind of movement variability is the central project of basically all athletes.7 This is in fact what most “technique” training consists of: how to trim all unnecessary movements so that what power we have can be channeled more effectively. And the advanced result is a joy to watch. When athletes succeed in translating their will so perfectly into motion, we exult with them, and are reminded there are such joys to being embodied as to make disease and disability sour memories.

But even getting to that point requires, as we know, years of practice. What keeps an athlete continually at the grind? Everybody likely has their own reasons. But perhaps the most general reason, to pick the low hanging fruit of etymology, is that athletes compete for a prize.

It’s human—no, animal—nature to discount rewards in (nonlinear) proportion to how far in the future we’re likely to get them. But it’s an interesting feature of human life that in some cases, we’re able to overwhelm such discounting factors by imagining a reward so large that we’re willing to work for years to attain it. It may be something like…well, heaven…or maybe something like a podium finish, if you’re an athlete. Things get iffy when we talk about “infinite” rewards and such, but winning at a worldwide contest like the Olympics, or even some ho-dunk competition where a poet could sing your praises for the historical record, still seems pretty damn important.

It turns out that subjective value and movement vigor are deeply linked. There’s work that shows how when faced with items we innately value, from sweet deserts to attractive faces, we tend to respond more or less vigorously, and that this vigor is reflected in different aspects of movement, from walking speed to eye movements. Fascinatingly, the reverse process also seems to be possible: we can even read back, just from saccade speed, people’s subjective valuations of items we present to them (that is, our saccadic eye movements tend to move faster when switching our gaze from vegetables to candy than from candy to vegetables).8

And in a roundabout way, this bridge between vigor and value brings us back to Pindar, with his emphasis on the importance of striving for victory. It’s not merely the case that those who move faster in a race are those who can move faster, due to their superior training. It’s often also the case, if you hear it from the athletes themselves, of who “wants the prize more.” And that psychological ability to assign supreme value to distant goals, which enables athletes to never cheat on their diets and run extra laps at practice, in some sense stands apart from all the training and genetics.

***

Along with the epinikian poetry that once accompanied them, sports don’t necessarily teach us what to value, they teach us how to value, and about the infinite ways we might apply vigor to get something we want badly enough.

And absent cathedral-building and crusades, projects once socially considered to be of “infinite value” (one definition of the sacred), we now look to the insides of stadia to provide a sense of both community and competition, and to glean impressions of vigor and value. In an age when many species of the sacred have gone extinct, sport is a sanctuary where it remains alive and well.

To give you a sense of his legendary reputation, Pindar is mentioned in a sonnet by Milton, following an old legend, as having the only house kept standing after Alexander the Great razes Thebes:

“Lift not thy spear against the Muses Bower

The great Emathian Conqueror [Alexander] bid spare

The house of Pindarus when Temple and Tower

Went to the ground…”

(Basically, Pindar’s house was sacred because the Muse herself resides there.) Milton, who wrote this sonnet during the English civil war, actually posted it on his door to discourage hostile soldiers from tearing down his house. Yes, he thought pretty highly of himself.

From the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Pindar’s Complete Odes, translated by Anthony Verity

Ancient Greece didn’t have much central religious organization—the country was populated by any number of cults. If there was any centralization at all, it was in the form of written mythic poems such as those written by Hesiod or Homer. Thus, the poet’s importance is hard to overstate, as they were perhaps the chief generators or collectors of traditional Greek religion, which was extremely flexible and always evolving. It’s then perhaps unsurprising that the word “cult” shares the same (Latin) root as both “culture” and “cultivate”. For the curious, Hamilton’s book “The Greek Way” goes into more depth on this.

The epinikian poet, the “victor’s companion”, sang for his own prize. Everything was a competition (agon) for the Greeks, so naturally, there were contests for poets too. In this way, writing poetry for the Games was part of the social infrastructure for ambition—if you were at all talented with language and wanted renown for it, one avenue for fame was to enter a poetry contest. The winning poet’s words would live on as part of the historic record, preserved alongside a player’s historic victory. And of course, the vigor of a victorious athlete is certainly a worthy substrate for a poet to shape with words.

If you’ve ever been to the doctor and they tell you to close your eyes and touch your nose, it’s testing your endpoint accuracy, which is typically associated with cerebellar function.

More specifically, a storm of error signals crawling up your spinal cord, through nerves called “climbing fibers”, and into your cerebellum.

There are sources of noise that can’t be trained out, caused by physical properties of neurons and cells membranes. Here we’ll limit ourselves exclusively to motor noise.

Reza Shadmehr at Hopkins, who’s worked a lot on subjective value and vigor, has some new ideas linking subjective value of rewards to the costs we’re willing to pay for them. The central insight combines classic models of foraging theory (a decision-making model) with motor control.