I recently learned of a new way to divvy up a soul. I was already familiar, as are many in western society, with the Greek conception which comes down to us strained through the one hand by Christianity, and squeezed, with the other, by the Enlightenment. The malformed view that’s resulted is that a soul is simply composed of Appetites and Reason, or relatedly, that we have an Animal Body and a Rational Soul, a division intended to explain why the sweet voice within us has trouble covering over the growl.1

Now, it may strike you as simple-minded to think that people are made of only Two Things. We’re capable of a wide range of behavior and belief, after all, so to limit our nature to only two essences can seem excessively constraining. It’s good to know, then, that the once dominant Greek models, the Platonic and Aristotelian, had not two but three parts of the soul, which thankfully give us more to work with. In some ways, we today have found it difficult to improve on their understanding.

This is because despite the centuries, an implicit view among scientists today who study the biological basis of the mind appears no more philosophically advanced than Aristotelian hylomorphism, the idea that the soul (or mind, as we now prefer to call it) emerges from the structural pattern of the body, the same way that though an axe may materially be composed of metal and wood, it’s the form of the object—in this case, that the metal is pudgy-shaped and has a weighty edge—that confers its “axe-ness”. 2 Likewise, within today’s “functionalist” view held by many (systems) neuroscientists, the various functions implemented on different neural structures are what are said to constitute the mind; it’s only within an abstract layer distinct from the biology that a mind can be said to reside.

So though we may not use such metaphysical lingo today, for Aristotle, the soul is nothing but the form of the body, a natural consequence of its structural arrangement. And as will soon be relevant, this ancient account once again divides the soul into three parts, which correspond to the various forms of living things: the vegetative (that which reproduces and grows), the sensitive (that which perceives and reacts to stimuli), and the rational—the last of which, he believed, only humans possess. You may have heard this part before.

And for the past few years, I’d satisfied myself with that modern elaboration of Aristotle which benefits from the innovations of Shannon et al.—that the mind is information carried by the physical tendrils of the brain, leaping across synapses and flashing through ion pumps, so that to speak of a soul is to discuss that entire buzzing process as it evolves through time, somewhat independent from the chemical substrate on which it runs.3 An independence which, at least in principle, may lead us to presume, or hope, that we’re not ultimately limited by our physical selves.

***

A: Astonishing, isn’t it?

B: What?

A: That information-theoretic approaches to the mind seem to have recovered that old split between mind and body…How odd it is, in our time, to hear fervent, technical-sounding hopes of one day being able to upload ourselves to a cloud…

***

Bill Newsome, a prominent neuroscientist (and a Christian) seems to hold something like this perspective, that if what we are is a dynamical pattern of brain activity, then it should be possible to preserve this pattern in the absence or degradation of the body. From here it’s a hop, skip, and a leap of faith to say that such a pattern is in fact preserved after death, especially if one already believes that “In Him we live and move and have our being”, as the Apostle Paul says to the Greeks. Newsome himself puts it this way:

Whatever life after death might comprise, it's not in my opinion going to be linked to the particular organic molecules that make up the neurons in our head. Because we can see what happens to those after we die: they rot, they decompose. If our identity is wrapped up in higher-level states of organization in the nervous system, then what's essential to any continued existence apart from those organic molecules is some kind of reproduction of that organization. And that is not crazy to think about.

Many relatively smart people do agree with him about this, including many neuroscientists. But, of course, where they would differ is the idea that the reproduction of our mental patterns is mediated by God. Other neuroscientists, most notably Kenneth Hayworth, are more inclined to think we’ll need to reproduce those patterns ourselves.

Contra Newsome, I think the view that our mental patterns are supernaturally reconstituted does, in fact, lead us into absurdities. I wonder what this view says about Parkinson’s patients, for example, for whom their basal ganglia—brain areas heavily responsible for controlling movement—degenerate before the rest of their brain. Is there, somewhere off in the ether of “being”, a lone pattern of former brain-firings bearing the instructions for a dance routine…err…unyoked from other brain networks that recognize when a wrong move is made? Though this could very well be true, it doesn’t seem to fit a standard picture of heaven.

One intuition I think this argument gets at is this: a heaven populated by mental fragments is rather dismal, even…horrifying. A heaven which is not whole, in the fullest sense of the word, doesn’t sound like heaven at all. And I think if we were to apply this intuition consistently, then it should not only apply to those parts of our mind which go on ahead of other parts; it should also apply for those individuals who go before their communities.

That is, what we classically intuit as important (which is no indication of the Truth, of course) is the preservation not only of our whole personal pattern, but our whole personal community’s as well, the one in which we presently pursue a good name; a social network whose approval means, quite literally, the world to us. This, perhaps, is closer to a standard view of heaven.

***

Which brings me to my recent acquisition. A philosopher and blogger whose writing I admire, Justin Smith-Ruiu, recently presented a series of fascinating questions, among which was a call for more ways of “arranging the cutlery” of the soul. Case in point of what he’s looking for is the Yakut model, which splits the soul thusly:

“Салгын-кут — literally “air-soul”, which is to say intellect or reason;

Буор-кут — literally “earth-soul”, which is to say the living body;

Ийэ-кут — literally “mother-soul”, which is to say tradition or culture.

Prima facie this seems to me at least as plausible a way of carving things up as either the Aristotelian triple-soul, or the Cartesian dualist account of the constitution of the person out of the exclusively rational soul on the one hand and the entirely non-soul body on the other, or indeed the prevailing scientific account today, which takes properties and capacities ascribed to the soul as emerging from the organization of the brain and central nervous system.”

(First of all, what? Tradition embedded in individual souls?) Smith-Ruiu goes on to map this view onto the Aristotelian account of the rational soul I raised earlier:

“…at various moments the air-soul has also been conceptualized, even in Greco-Latin-Arabic-European tradition, as communal, perhaps in more or less the same way as the mother-soul. That is, in a transcendental theory of Ideas, or in Averroës’s theory of the unity of the intellect, the Idea of, say, Triangularity or of Justice is not something we possess as individuals, in our minds, but some kind of shared resource in which we are granted a fleeting usufruct.”

Which reminds me of JBS Haldane’s line from “When I Am Dead”:

“But I notice that when I think logically and scientifically or act morally my thoughts and actions cease to be characteristic of myself, and are those of any intelligent or moral being in the same position; in fact, I am already identifying my mind with an absolute or unconditioned mind.”

But although Smith-Ruiu’s connection of Aristotle’s account of the soul (as representative of Western thought about collective minds) with the Yakut’s is an extremely thought-provoking one, I’m not sure it digs to the deepest part of this metaphysical exchange between the Greeks and Yakut.

That is, we might just as validly compare the Yakut model with Plato’s, and I think this comparison might reveal an important similarity between their views of the soul—they both point out an inherently social aspect of individual human personality. And I hope it’s not too outrageous to posit that this interesting overlap between cultures suggests a kind of posthumous survival we can rationally consider.

Plato’s model is not that far off from what we’ve seen so far, and in fact resembles almost exactly the first view I presented, the one which contrasts the Appetites and Reason. Plato has a third part to his model, a soul-part he calls thumos or “spiritedness”, which drives us to seek honor and good reputation, and avoid shame.

In some sense this is directionally the opposite of the Yakut model of “mother-soul” or tradition, which looks to the past; thumos looks to the present and future. The first is the voice of the ancestors, or more concretely, the voice of those who speak with their ancestors’ voices4; the second refers to the urge to seek the applause of our peers, our polis, those who occupy the same sphere of life as us and whose approval we value.

A viable unification of thumos and the “mother-soul” may be impossible to imagine. The directions just seem to cancel out. But if you’ll allow me, I’ll try to meander my way to it.

If the realm of the rational community is impersonal and objective (as with Aristotle and Haldane), thumos and the mother-soul seem anything but. As far as I understand them, the latter both appear to respect uniqueness—the mother-soul is composed of the various voices who are responsible for one’s present culture; as Pirsig writes of our own:

“We see what we see because these ghosts show it to us, ghosts of Moses and Christ and the Buddha, and Plato, and Descartes, and Rousseau and Jefferson and Lincoln, on and on and on. Isaac Newton is a very good ghost. One of the best. Your common sense is nothing more than the voices of thousands and thousands of these ghosts from the past.”5

…And thumos is what motivates someone to seek public outlets in which to exhibit their virtues—which are often credited to that particular person, and add to their sense of esteem.

A soul-model which takes them both seriously ought to at once balance the tension between how tradition a la the mother-soul, something collective contained in an individual, is linked to thumos, how an individual gains the esteem of a collective.

The best piece I’ve encountered articulating the unification I’m looking for is perhaps an essay by T.S. Eliot, titled “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (which I can’t recommend enough). To summarize its ideas in the vocabulary we’ve built up so far, I think Eliot would say that it’s impossible for a talented artist to produce truly thumotic art without first enlarging their mother-soul:

“Tradition is a matter of much wider significance. It cannot be inherited, and if you want it you must obtain it by great labour. It involves, in the first place, the historical sense, which we may call nearly indispensable to any one who would continue to be a poet beyond his twenty-fifth year; and the historical sense involves a perception, not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence;”

He goes on to describe the whole, interconnected nature of his notion of tradition:

“…what happens when a new work of art is created is something that happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded it. The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them. The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered; and so the relations, proportions, values of each work of art toward the whole are readjusted; and this is conformity between the old and the new.”

What does this suggest about the mother-soul? If we emphasize the variation between the types of stories people consume, we may superficially think one person’s mother-soul is likely to substantially differ from another’s.

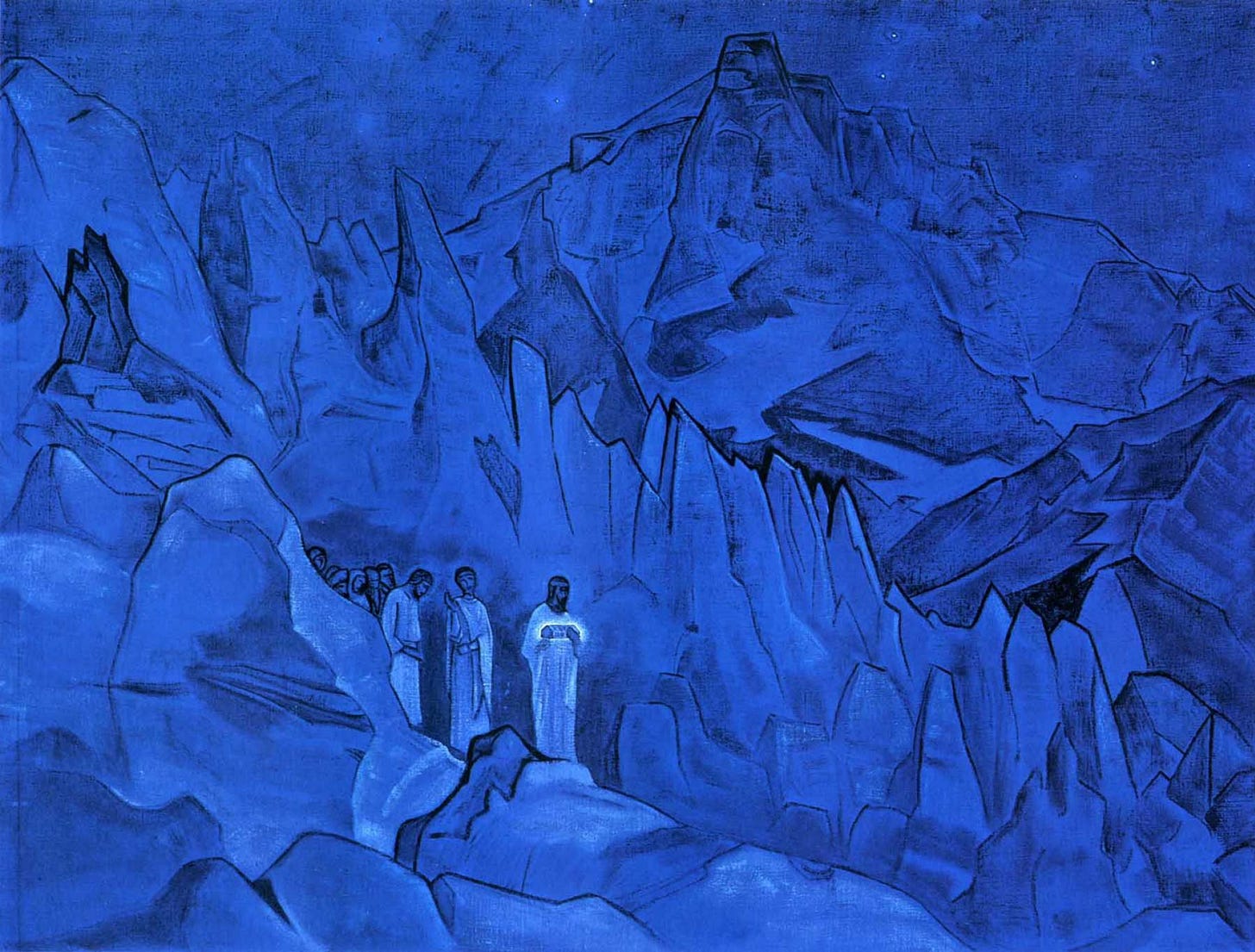

An astronomical metaphor may be helpful here. I read Eliot as making the point that the whole “night sky” of tradition, the sum total of great human art, is all there, complete, at any given time. The past is always with us, even if we don’t recognize it. Everyone’s mother-soul is the same to the extent that Tradition is the same for everyone in a given zone of culture— but various elements of that Tradition still need to be individually discovered for us to become aware of the “presence of the past”. To enlarge one’s mother-soul, in this view, would consist of uncovering more and more of a culture’s map of influences for oneself.

Staying with the “night sky” metaphor, perhaps it’s the case that all an act of media consumption does is to make a constellation and its neighbors visible for a particular person. This explains why anyone who aims to fly up to the heavens should have their stellar maps straight.6 An artist rarely, if ever, simply launches into a void.

Some final remarks

Finally, it may be worth noting that in a society in which the night’s glowing dots are ancient heroes (within a philosophical system where the world we have immediate perception of is generated by the mind, as modern neuroscience tells us and as many ancients believed), to gaze up at the stars simply becomes another way of viewing the “monuments” of human imagination.

To look up at these stars for guidance or strength would then have new significance: it would be to draw from a shared social reserve of honor, free for any living person cognizant of that culture to do so. Not least for the artist, whose greatest aspiration—the fulfillment of their creative thumos, that which grants them a type of immortality—is to alter the sky itself, and contribute the whole or part of a constellation.

If all this were more widely believed in our own culture, perhaps Milton would be Betelgeuse and Shakespeare the belt of Orion…but imagine, for a moment, many light-years further on, in the remote past, those who crafted their souls into the pottery of the Paleolithic, and those who hungrily sketched herds of black bison on dank, fire-lit walls. They’re all up there too. And they surely far outnumber those dots of light we can see.

I don’t know about you, but that sounds like a heavenly community to me.

Paraphrased from Report to Greco by Nikos Kazantzakis

(as opposed to the forms of other kinds of blades)

A more comprehensive treatment on my views on this would require more space than I’m sure my readers wish for. I’ll settle for something pithy and poetic, for now.

In elder-led societies, common all round the world, even in our own culture (in the form of a senate, derived from senex—“old man”) the ancestors and their living representatives are separated by a thin veil.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Importantly, creatives need only enough acts of consumption as will benefit our launch. Eliot again:

“It will even be affirmed that much learning deadens or perverts poetic sensibility. While, however, we persist in believing that a poet ought to know as much as will not encroach upon his necessary receptivity and necessary laziness, ...Some can absorb knowledge, the more tardy must sweat for it. Shakespeare acquired more essential history from Plutarch than most men could from the whole British Museum.”

Nice piece. I think we can make some distinction between "soul" in the broad sense of "what makes you the type of being you are" vs. the more narrow sense of a kind of causal explanation for what makes you speak and act, with the latter being an idea that developed in cultures with a tradition of philosophical inquiry into the ultimate principles of the world, particularly ancient Greece and India. In that case, there is the question of whether something like the mother-soul, a shared realm of ideas and tradition, is having an immediate causal effect on me distinct from bodily structure or any personal soul I might have (something like a collective consciousness or unconscious), or whether it's important because of the way it shaped my body/mind in the past, the "fingerprints" it left on them. Imagine my body/mind in its current form transported to a parallel universe with the same laws of nature but with no other humans, cut off from all further causal influences from my home universe (including any sort of psychic influence from a human group consciousness)--would I still retain my personality, reason, creativity etc. because of those fingerprints of human society left on my present form (at least until I went crazy from the isolation), or would I instantly become a different sort of being without the ongoing influence of the rest of humanity?

BTW, it's my understanding that there is a key difference between the way Aristotle thought the mind was the form of the body and the ideas of modern scientific thinkers who see the mind as a pattern of information in the body. In terms of the distinction between "strong emergence" and "weak emergence" that philosopher David Chalmers discusses in his piece at https://consc.net/papers/emergence.pdf , the modern thinkers would usually be arguing for weak emergence where my purposeful behavior can in principle be accounted for based just on the laws of physics acting on the arrangement of particles/fields in my body and its immediate environment (Chalmers seems inclined to accept this is true about behavior, though he thinks subjective consciousness is a different matter). Aristotle seems to have argued for something more akin to strong emergence where forms like the soul can exert a top-down influence on the matter of the body which can't be accounted for in terms of the lower-level physical properties of the individual parts and the way they interact. See the discussion starting on p. 326 of https://ancphil.lsa.umich.edu/-/downloads/faculty/caston/epiphenomenalisms-ancient-modern.pdf which talks about his reasons for rejecting the ancient "harmonia" theory of the soul discussed earlier in the paper, the idea that the soul is akin to the musical properties of a lyre which are assumed to depend only on the lower level properties of its parts, like the noises made by individual tuned strings (Plato also criticized this idea in his dialogue Phaedo).

Great. Will be a part of my memory for a long time