“For you cannot know what is not - that is impossible - nor utter it; For it is the same thing that can be thought and that can be.” - Parmenides

I.

There was a woman who’d often come by, two kids in tow, to my grandparents’ house in the Ethiopian countryside. The older child was younger than me but large enough to play soccer, and the two of us, along with my brother, spent the better part of a summer wearing a ball down to its inner lining. His name was Yoseph, and his younger sister, then about four or five years old, was called Mita, an affectionate Amharic nickname used to refer to young female children.

At some point that summer, I asked Yoseph about his sister’s “real name”—her government name—not to refer to her by it, but out of curiosity. Yoseph matter-of-factly replied, astonishing my teenage self, that she didn’t have a name like the one I expected. “Mita is just her name.”

Now, this wasn’t a case of an older brother being oblivious. Yoseph’s innocuous response was instead the result of a grim practice in the countryside. Rural Ethiopia was (and still is) fighting to keep infant mortality down, and parents often kept from naming young children born with uncertain futures. This naming practice is by no means unique to Ethiopia—though there are variations, it’s shown up in many places with high infant mortality.1

I hadn’t deeply thought about the implications of all this until recently. And when I did, I had a hard time imagining the development of a child who was named in this way, and could guess at why it was so. It seems an odd existence, as if because of the emotional distance the parents keep, the child lives in a state of existential limbo, waiting to have their presence ratified by being given a permanent name.

Part of my weakness of imagination, I think, stems from a strong intuition about what naming does—specifically, the fact that when something is named, it’s cemented into mental existence. As Adam Gopnik describes in his book Winter:

The first thing that the earliest polar explorers did was to name the ice shelves and coasts — naming them after their patrons and their patrons’ moms — and then the very next thing the very next group of explorers did was to change the names, naming those same things after kaisers and their daughters. Names are the footholds, the spikes the imagination hammers in to get a hold on an ice wall of mere existence.

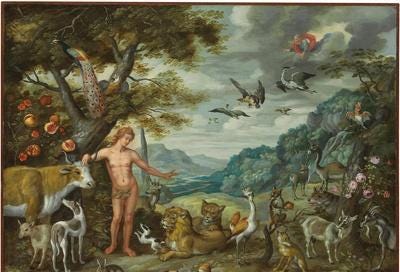

The Adamic act, one might call it — not in light of this speaker but of that first Adam, whose entry-level job was to name the animals, calling a bear a bear and a snake a snake... Giving the animals names is to call them out of mere existence into mind [emphasis mine]. That act is the thing that makes the world humane. It gives structure and meaning to natural events that in themselves contain none.

So if naming helps us make sense of “merely existing” things, stabilizing them somehow, the downside is that when the named things are gone, they doubly impact the world through their loss (than if they weren’t named). And when even the lives of children are fraught, norms reflect this instability. Perhaps it is reasoned correctly that we’re better off not naming ephemeral things, especially if we know the pain of loss is likely to follow.

This pain of loss, when a name no longer picks out its intended referent2 in the real world, might have a lot in common with the way a tongue feels for a missing tooth or an amputee tries to scratch a missing limb. We could even link this feeling of loss to what is called the “emptying” of a name, a classic issue in the philosophy of language. When a name is emptied, the label itself persists without the promise of the referent’s reappearance, a lone tag with no real object under it. This is likely to happen when we name something unstable, like a child in a high infant mortality environment, or more generally, things like super-heavy synthesized elements.

It’s worth pointing out that in science, there’s more a feeling of error than loss; when an element is named too quickly and its namers realize it doesn’t exist stably, they feel the error of ascribing a name that refers to no-thing out in nature (though the error might come with some pain!). So the means of emptying a label are through one way, real death, and through another, the death of some hypothesis. But the pain of “emptying” is something to be sought after in science, we are told, not avoided, unlike in more familiar circumstances.

II.

If we look at history through the lens of naming, we can think of our willingness to name a thing as a function of our perception of its intrinsic stability. By stable I mean existing singly and for a long time—I have in mind geological events—or for a short time but with regularly repeatable instances, like with many biological events. Conversely, ephemera are things that appear once and quickly, or appear many times but in an inconsistent or variable manner.

The easiest things to name tend to already be somewhat definite before they’re given a name. The ice shelves that Gopnik writes about are a good example, so clear and distinct the label practically sticks itself. But naming things with more ephemeral character is risky; there’s always the chance that you’ve misnamed them, and your name will continue on without its real referent.

Is there something like a threshold of stability, below which we don’t bother with naming something, and above which a thing merits a title? It seems like there is, and that this threshold can change. Consider the worldwide decline in infant mortality. Young children are no longer considered ephemera, and the value of life has risen in conjunction with the scientific understanding that contributed to the reduction of infant mortality in the first place.

In fact, it’s probably fair to say that the single biggest influence on the lowering of this naming threshold is the scientific revolution. And to get a grip on what science has achieved, we can trace the illustrious, even mythological, history of naming that reaches in time far before the Enlightenment. We can justifiably think, with just a touch of hyperbole, of contemporary science as being continuous with the Adamic act of naming. (This isn’t an original idea—it goes back to pre-Enlightenment figures like Roger Bacon, who conceived of the Fall as a forgetting of knowledge that granted us immortality, and that through the examination of the natural world in an imitation of Edenic science, we’d someday recover the path back to our blissed state.)

The Adamic act is, as you might expect, much simpler than the science we have today. At its most basic level, this ancient naming process is comparable to how children tend to start learning language by acquiring nouns, perhaps fitting if we think of Adam as not only the father but as representing the firstborn of the human race. And it’s an interesting exercise to picture, not necessarily all our hunter-gatherer ancestors, but the groups of early humans who could speak, as first having to converge upon proper nouns for the animals and plants they encountered.

How did we get from this ancient (or early) stage to our current one? If we peer along a single dimension of complexity, putting aside more causal pictures of the cosmos (i.e. relations between names), there are more names floating around than ever before. Today the scientific method pervades ever more granular units of reality, and there are more named objects than single human minds can remember.

What we notice has happened in our current scientific society is that our relationship with ephemera has changed. In a sentence: we no longer think of the natural world as composed of ephemera. Better sensors and recorders mean objects that used to flit by us unawares are now logged by mechanical eyes and memory. We can snap pictures of light using cameras that make even the Brownian jitters of the atomic world stand still. We can name elements that last for fractions of a second (but provisionally so, first, since we’re unsure of their veracity). We have a databank with millions of discovered protein conformations.

What has happened is that ephemera still occur—events which happen once and quickly, or many times without obvious pattern—but they’re given constraining explanations now, where before they might have remained simple points of observation, merely existing, as Gopnik put it. Or alternatively, ephemera were placed within some unconstrained framework, in which some deity or spirit was responsible for vaguely connected events. These unconstrained models, which we call mythology, didn’t lessen the sense of ephemerality in the world, nor did they mean to. The old way of dealing with ephemerality wasn’t to control it. Natural ephemera were bargained with and cajoled into going our way, and the hidden cause, the spirit, was left unconstrained—a person in their own right—so a negative outcome to a blood sacrifice for an ephemeral event like rain was explained as easily as the positive, as the result of some capricious god unsatisfied or satisfied with their offering.

These days, however, our theories provide constraining explanations, providing a broader context that stabilizes ephemeral data points. Scientists often intentionally create ephemera in their labs, events that occur nowhere in the universe except in some isolated box in which the experimenter has utmost control, a process relied upon to reveal truths about the wider world. And this system works. We really do deal better with ephemera by willfully altering conditions that lead up to and around them, updating our names (i.e. jargon) and name-relations when our predictions of what happens in those boxes prove false.

III.

What Gopnik doesn’t mention is that in addition to the task of naming, the biblical God of the story also charged us with dominion, to subdue the natural world. So it’s tempting to think of the Adamic act as, in part, emerging from a desire for stability in our environment. After all, doesn’t naming go hand-in-hand with control?

Yet we blunder if we think names somehow actually turn ephemera stable—our names don’t actually change the world “out there”. Everything in nature, including mountains and the flowers on them, is really varying degrees of ephemeral, all one-of-a-kind, all transitory in the scope of timescales beyond our individual lives. Stability is imposed by the mind, the place from which our theories originate and in which they remain. We might think of the sense of stability as born from perceiving commonalities and distant unities—patterns from which our compressive minds produce anchors we call names.

To illustrate this, we can imagine a mayfly as never perceiving a sense of stability—its life is too short for experience to be worth compressing. On the other hand, we could imagine some hypothetical being whose perfect memory leaves no need for compression. As somewhere between a mayfly and a god, however, I can’t help but resist the implication that our ability to name makes us a good fit for world domination, as a literal reading of Genesis makes us out to be. Gods seem most apt for that task; why abdicate and leave the job to some hairless upright primate?

Borges evocatively addresses the question of perfect memory in his short story “Funes the Memorius”. Funes’ mind is awash in particulars: “dog” recalls every dog-like, furry four-foot entity he has ever seen, and further still, views from the side and from the front are, to him, distinct dogs. Although he can remember every name he’s ever heard, Funes must relive every specific enunciation of a given name; his episodic memory is so detailed that he remembers the unique instants of when a name is said aloud. He makes attempts at a naming system for his massive log of experience, only to discard it out of consideration for his too-short length of life, and for the fact that it would be useless. No one else has his memories to refer to.

And who would make the best use of such perfect memory but a god, with perfect memory and long life to boot? What Borges’s story convincingly shows, I think, is that an entity with perfect memory has no need for names, since all referents would be close at hand. If we take the biblical deity to resemble Xenophanes’ bodiless god, who could shape and impact the world with just a thought, possessing only referents would be rather handy for such a being, who could express its will simply by beaming visions of events directly into the minds of lesser beings. And in a pinch, it could provide names to appease those creatures with a tendency to get nervous when thinking about ephemerality.

So no, not domination for us. But I do like the picture of Homo sapiens as stewards. A god sees much but with little involvement (just look at the state of things), and the mayfly is too involved in life to really see the bigger picture. But names allow us to strike a balance. As animals that look around and find themselves transient like the rest, but with the ability to fix in our minds some notion of the whole and its parts, generals and particulars, the role most appropriate for us seems to be that of a gardener, tending here, tending there, with an eye for detail yet keeping in mind the wider scene.

The rural naming practice, I came to understand, involved giving an infant a provisional name based on the child’s appearance or some idiosyncratic behavior of theirs, like what they like to eat—once, for example, I met an Oromo teenager named “Boqola”—“Corn”. If or when a child reaches adolescence, they are given a new, more lasting name, or their original name may stick. In many cases, the use of the provisional name would be retained, going beyond just a lifelong nickname for loved ones to use, to end up on official IDs (imagine having a mayor with a legal name like Timmy or Jon-Jon. Though I suppose it makes them approachable).

I emphasize real-world referent here to separate it from the larger sense of the word “referent”, since names don’t necessarily refer only to real-world objects. A name could refer to the representation of a real object (the mental picture of a horse), or the representation of an unreal object (the mental picture of a unicorn). In this piece, in all cases when I use referent, I mean real-world referent.