I. The situation

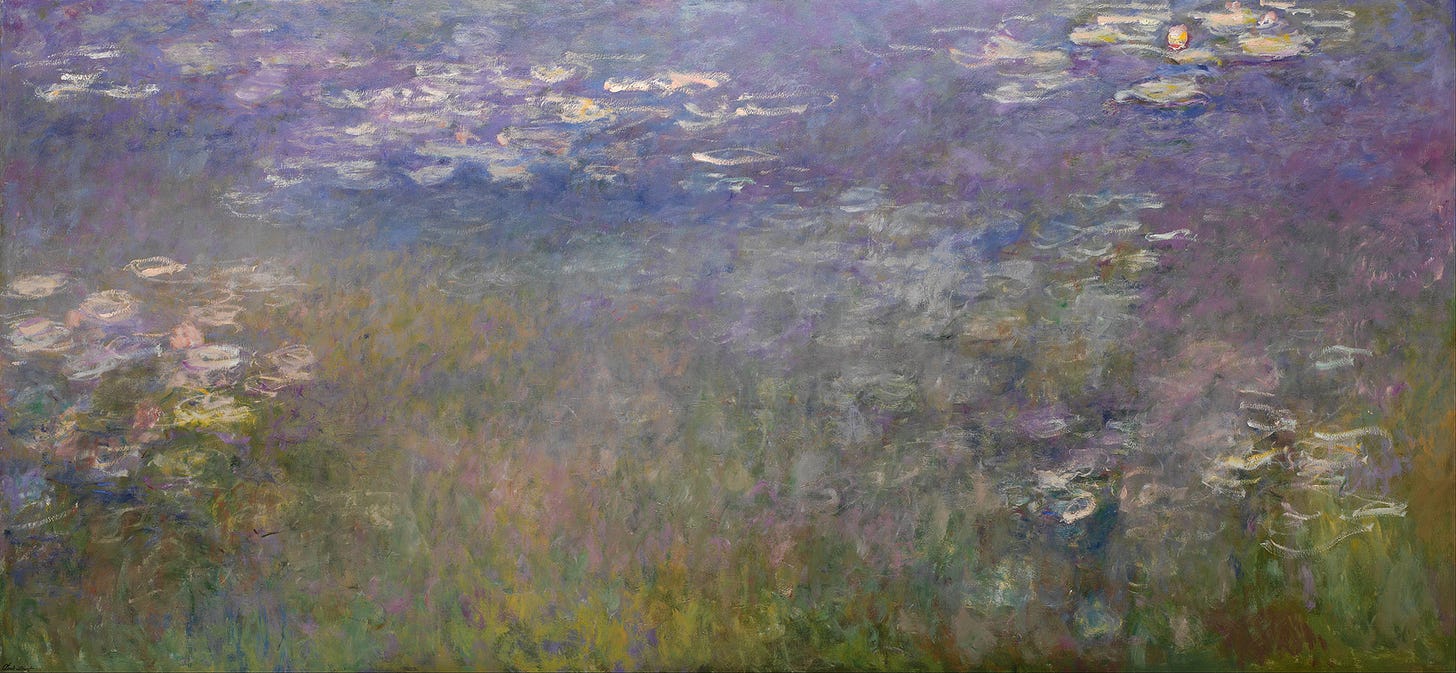

Imagine sharing society with beings whose senses differ just slightly from our own: their hearing mostly overlaps with ours, but descends to lower frequencies; their visual systems make no use of long wavelengths of light (think red), but enjoy shorter ones, including ultraviolet. Naturally their culture reflects these shifted capacities—this sympatric society has music filled with sounds we can’t hear, and paintings with grades of color we can’t see.

Meaningful communication with these beings would be possible, however, since besides sharing the relevant laryngeal anatomy there is also (as we said) plenty of sensory overlap. Still, living with them would be like a permanent visit to a different country, a country whose way of life we can never quite crack, and where a missing photoreceptor and a too-short cochlea (at the very least) serve as barriers to cultural mixture.

Well, as it happens, this sort of mixed society is the setting of Roger Zelazny’s book This Immortal, which tied for the Hugo Award with Dune in 1965. In it, humans have been rescued from a world-wide atomic war by an elder race of aliens called Vegans (which hail from the planet Vega, not Vegetable), and we find, first thrillingly then disappointingly, that though Vegans have made much of our once-barren solar system habitable, the humans who live with them have been relegated to a labor force—a comfortable labor force to be sure, but a labor force all the same.

The main reason for this, we are told, is the incongruence between human and Vegan sensory worlds.1

Students of biology will be familiar with the concept of an umwelt, a term which refers to an organism’s unique sensory environment.2 It’s often easiest to conceive of alien umwelten using our own as a frame of reference—this species sees higher or lower energies in the light spectrum, that species has their hearing range above or below ours, and so on. For the sake of a handle, we could call this comparison the “umwelt-gap”.

Now, this rough and ready term quickly runs into problems. There are many umwelten for which references to our own make little sense. Ed Yong’s most recent book An Immense World is full of such examples: what sort of “vision” can we be said to share, for instance, with the 200-eyed scallop, that miniature Argos Panoptes of the sea whose brain forms no scenes but still watches for movement; or with the single-cell, Emersonian “transparent eyeball” that is Synechocystis3; or, just among Mammalia, with the hearing-based spatial senses of echolocating creatures like bats and cetaceans?

These strange examples seem to make shambles of our intuitions, out of which the “umwelt-gap” term emerged. But I still think the idea is useful. By abstracting umwelten into a “sensory-space”, we can conceive of our sensory differences with other creatures (real or imagined) in the form of a distance.4 And, more importantly, keeping this distance in mind may let us track when our imaginations flutter free to fill the gap.

But isn’t imagination a good thing, helping us to cross sensory gulfs? Yes, I’d say, but only to an extent, a limit which we’ll try to define shortly. The trouble is, our imaginations also make certain sensory worlds appear more familiar than they are, especially those examples where we have a sense in common with a creature whose capacities are “extensions of” or “shifted from” our own.

Case in point: wouldn’t it be silly to say that because we have a decent sense of smell, the world at a dog’s sensitivity must simply be “more smelly?” Or when we picture the umwelt of a creature who can hear below our normal range—and we believe we can imagine what that’s like—is it not the case that our imaginations are merely filling in those frequencies we can’t hear? And have we succeeded, just by imagining it, in actually hearing into those lower frequency ranges?

Of course not. We’re misled by simpler self-comparisons into thinking our imaginations help us bridge the gaps those comparisons reveal. Only once we catch ourselves in these understandable cases of empathetic absurdity can we see how the examples of umwelten which completely throw us off, like those of scallops or bats, simply cast the weaknesses of our mental projections into sharp relief. Such examples stun our imaginations into immobility; like the proverbial roadrunner, we find we’ve been leaping over a void all along.

The question practically asks itself: is this void between umwelten crossable? Like really, truly crossable, and not only in our imaginations? The Vegans would have us think not. But the servitude of our species hangs on our answer!

So let’s contend, here and now, with the limitations which prevent sentient creatures from understanding each other across sensory gulfs.

II. The situation is fleshed out

The umwelt-gaps I mention above seem insuperable, at present, because such gaps result from sensors and downstream processing which vary considerably, often innately, between animals. Let’s call these sorts of gaps—between the “human” umwelt and those of the creatures mentioned—hard gaps. Many discussions about umwelten take hard gaps to be the primary (or even the only way) of talking about them.

So-called hard gaps typically have hard consequences: there are patches of the universe which, without the requisite sensors, can’t be detected, and therefore go unexploited (with potential effects on survivability). This is worth emphasizing—throughout the biological world, unless some signal in the world is able to enter the mind of an organism, that organism typically can’t make use of it.

But the gap between humans and Vegans in this “hard” respect is small enough that it doesn’t present an obstacle to co-survival—only to the formation of a collective culture. This is what makes the Vegan case interesting: it suggests that when we have hard (though small) umwelt-gaps between species that both possess complex culture, hard gaps can have soft consequences. That is, while humans on a Vegan planet can certainly eat their food, take their orders, and do their manual labor, we’re barred from substantive involvement in that alien culture because of our biological differences. We are “non-Vegan immigrants” with no hope of assimilation.

And that terms like assimilation make sense in this context, I think, touches on the useful notion of a soft, or cognitive, umwelt. The same way a “hard” umwelt is the space of things an organism can perceive and make use of, a “soft” umwelt is the space of things it can think about.

Normally, soft umwelt-gaps are surmountable. Anyone who’s lived at length in a country they aren’t native to can attest to its mind-warping effects. Gradually—and with significant effort—you begin to see the world like them. Eventually instead of mapping their language to the one you already speak, you begin to think entirely in this second language, a process culminating in the debut of this adopted language during sleep.

What does it mean for soft umwelt-gaps not to be surmountable? This is what I take Wittgenstein to mean when he said “If a lion could speak, we could not understand him.” It’s not only in terms of our sensory apparatus that we differ from lions, it’s what those senses are suited for—a particular way of life, the things animals care about in their environment.5 Granting a lion speech without acknowledging those more fundamental differences is, well, a little nonsensical.

So, using our new terms, humans on a Vegan planet find themselves in a situation where the two types of umwelt, hard and soft, overlap; humans lack perceptual and cognitive access to Vegan cultural life. And the central (and I think correct) assumption in This Immortal is that humans lack cognitive access to Vegan culture because we lack perceptual access to its cultural artifacts6. The direction of dependence is one way—what we sense provides the raw material for what we think.7

III. The joys and limits of umwelt expansion

Ok, so we have some terms. But how do we get from one umwelt to another?

A common way of crossing hard umwelt-gaps is by using instruments. Their most powerful function is detection: instruments face reality in a manner analogous to our so-called end-organs (the retina, tongue, skin, etc.), which transduce some physical signal—light, chemicals, whatever—to the code of the nervous system, making information about the environment available for use by the sensing organism.

There are many different sorts of instruments, in this general view. The classic usefulness of a hunting dog, for instance, results from its superior sniffers; likewise, my relatively dumb (and less friendly) spectrum analyzer can tell me of radio signals in my area, presenting them on a simple graph of frequency and amplitude, variables I can recognize and readily make use of.

This generality of instruments seems justified according to Clark and Chalmers’ extended-mind thesis, which argues that the use of certain external aids blurs the distinction between self and instrument—a notebook may be considered an aid for thought, but it also seems correct to say that it’s where our thinking takes place, a place without which ideas of very high complexity would lay beyond reach. Similarly, maybe the sniffers and spectrum analyzers from my example extend our sensory capacities in a similar fashion—they enable us to exploit parts of the world formerly invisible from the umwelten we’re born with. (More on this later.)

And how do we cross soft umwelt-gaps? They clearly require more than just detection. Cultural gaps, as prime examples of soft umwelt-gaps, seem to be crossed most securely (at least, so far) by anthropologists-cum-linguists, people who have made intense study of two ethnic cultures and can identify points of overlap and difference between them. So we might say that soft gaps are traditionally bridged by translators.

But does all this mean that when I use instruments, the physical signals they process and display have actually expanded my hard umwelt? Or, because of translations, that I can imagine all the world’s “cultures” to be included as part of my soft umwelt? Well, yes and no.

Going to a Vegan museum and peering through a UV camera, or wearing hearing aids at Vegan concert halls, are all very well possible. If the Vegans were a kinder race— patronizing in the fullest sense—maybe they’d let us do this. Likewise, there are plenty of ancient texts translated to the lingua franca of any given period of history; it’s possible today to read ancient Latin texts in a myriad of English translations.

But here’s the clincher: could I make a Vegan painting equipped with special cameras? Or, by loose analogy, write a Latin epic poem by reading the Aeneid in English? I doubt it.

These reductios point us to a side of cultural involvement we’ve ignored thus far. The production of meaningful cultural artifacts—art, in other words—vitally depends on the close perception of the “raw material” being shaped, whether colors or words. The creative process is extremely sensitive to the distortions to this “raw material” which our aids introduce. And as helpful as they are, our aids, do, in fact, distort things, and the distortions will be immediately obvious to a person not relying on those aids.

This has some interesting implications. It would seem that what makes a cultural product trustworthy is when it’s created in an umwelt that all its consumers share. And we know disdain would be the likely fate of a human artist on a Vegan world because we have our own examples of a mismatch between creative and consumptive umwelten much closer to home. We call it cultural appropriation.

I suspect cultural appropriation feels bad primarily because it’s done badly. And we’ve already covered the reasons why it’ll almost always be done badly. The way to do it right, as we’ve also covered, is pretty hard; it actually requires effort to slip into a cognitive umwelt one isn’t native to. Merely translating “oh, this color on the cloth means this” isn’t really enough. If the Congress members who wore the kente cloth were to speak decent Ashanti, or had thoroughly studied Ghanian culture, maybe their stint would have come across better.

So when someone dons for a day the apparel of a culture to which they have little or no connection, our instinctive reaction is often distrust. But it could also be why many literati dismiss the writing produced by LLM’s (so far), tools which seem to have bypassed the worlds about which humans write, themselves writing in the humming darkness of a server farm.8 The refrain for all of these cases is the same: What do they know of our world?

IV. The future of umwelt-gaps: or, how I learned to stop worrying about umwelt-gaps and love technology

One criterion of Clark and Chalmers’ extended-mind thesis is that an aid which “extends” some ability of ours should be tightly coupled to us, such that it should be as smooth and easy to use as one of our own organs. I’m not sure the tech we currently use to expand our hard umwelten satisfies this requirement. The distortions instruments add to the “raw material” of reality seem to detract from the kind of thing we care about, the direct experience of seeing UV in much the same way as we already see other colors.

So I’d like to backtrack a little here, for the sake of that human artist on the Vegan planet. There’s no reason, in principle, why a sufficiently advanced sensory aid wouldn’t help her produce Vegan art that could be appreciated by Vegans. But the prosthetic she needs would have to be advanced.

Such a prosthetic could be something like the “Science Eye”, an implant designed to be wired straight onto the optic nerve, much like how hearing aids work by hooking up to the auditory nerve. The Science Eye may initially be plagued by the same weaknesses as its auditory analog, which still isn’t well-suited to capturing all the dynamics of music, like the frequent sub-second changes in loudness, pitch, and several other dimensions. Our visual environment, similarly, changes constantly in brightness, color, and so on. But it’s feasible these challenges may eventually be worked out.

There are even more issues to visual prosthetics. Color perception in many animals works by the principle of opponency; the sensation of one wavelength of light inhibits the sensation of others. This added complexity is completely bypassed by a UV camera, which merely blocks out every wavelength outside the UV part of the spectrum and digitally transforms the resulting image into visible light we can see.

So it could be that for a visual prosthetic to be tightly coupled enough with our nervous system to give us a direct experience of seeing UV, the umwelt prosthetic we end up with—if we could even call it a prosthetic, then—would have to be biological.

And it turns out that, as with space travel, the first travelers between (hard) umwelten are other animals. One such inter-umwelt traveler is a bichromat-at-birth named Sam the squirrel monkey who, after receiving the gift of a third photoreceptor, found he could pick between differently-colored fruit that to his fellow squirrel monkeys looked indistinguishable. (Sadly, Sam can’t tell us what this transition was like.)

Neither does it seem that the barriers between soft umwelts will remain standing, AI translation is doing spectacularly well. Eventually neural networks trained on English text, and which can satisfy an advanced (say, >90th %) speaker, will communicate and even merge with similarly specialized networks trained in Latin, or Spanish, or what have you. Hell, a single model could probably do it all.

Regardless, in the future when such translation becomes possible (which looks increasingly likely), maybe you wouldn’t need a person to study for years to perfect their grammar or word usage (or at least, if they do, it won’t be out of necessity but for personal development). Translation, too, may turn out to be a technological problem.

V. What approaching reality means

Given how our cosmos seems to be peppered with perspectives, each vantage point making use of some physical signal as evolution deems useful for their survival, those who attempt to approach reality “as it is” have their work cut out for them. It would seem that the simple, but not easy, way forward is to configure our minds with as wide an array of sensors as we see evolved in the natural world.

Imagine artists with access to all the signals which are constantly floating around us, producing art to a community which shares their senses! Increasing degrees of artistic freedom would certainly be among the most liberating uses of technology, allowing dimensions of taste which we (right now) can’t even imagine.

But as Sam the squirrel monkey shows, much of our current makeup would have to change to accommodate these new abilities. Perhaps this would require too much of a change, and our future minds would be unrecognizable compared to the primate brains we possess today. Who knows, the umwelt-gap between the people of today and of the future might even be as large (and dizzying) as the one between us and scallops!

But this is all very far away, just in the realm of the remotely possible—all in our imagination, in other words. I hope I may be forgiven for my more hare-brained musings, but if you’ve made it this far, dear reader, perhaps no such forgiveness is necessary.

As Milton wrote,

“But apt the Mind or Fancie is to roave

Uncheckt, and of her roaving is no end;…

…Therefore from this high pitch let us descend

A lower flight, and speak of things at hand”

Paradise Lost, Book VIII

And what do we have at hand? Each other, of course. That our imaginations are pliable enough to take the shape of other cognitive umwelten is well worth appreciating. Even if translations don’t offer us a complete grasp of finer cultural details, they still give us the impression of alien, but comprehensible depth; they tell us there’s far more to human imagination than the ways of thinking we’re used to.

So it’s good to travel, to read, to engage with other cultures. Yes, yes, hardly anyone needs to be told this. But it’s a hope of cross-cultural metaphysical exchanges (like on types of souls) that in addition to mapping the sheer diversity of imaginative output our species is capable of, we might also understand those concepts which are basic to human thought itself, if such exist—ideas to which human thinkers and societies have been ineluctably drawn to throughout history. And while we wait and work to bring the hard future closer, this softer project certainly has plenty to satisfy our curiosity.

***

“Let me take that flower from your hair. There. Look at it. What do you see?”

“A pretty white flower. That’s why I picked it and put it in my hair.”

“But it is not a pretty white flower. Not to me, anyhow. Your eyes perceive light with wavelengths between about 4000 and 7200 angstrom units. The eyes of a Vegan look deeper into the ultraviolet, for one thing, down to around 3000. We are blind to what you refer to as ‘red,’ but on this ‘white’ flower I see two colors for which there are no words in your language. My body is covered with patterns you cannot see, but they are close enough to those of the others in my family so that another Vegan could tell my family and province on our first meeting. Some of our paintings look garish to Earth eyes, or even seem to be all of one color—blue, usually—because the subtleties are invisible to them. Much of our music would seem to you to contain big gaps of silence, gaps which are actually filled with melody. Our cities are clean and logically disposed. They catch the light of day and hold it long into the night. They are places of slow movement, pleasant sounds. This means much to me, but I do not know how to describe it to a—human.”

“But people—Earth people, I mean—live on your worlds…”

“But they do not really see them or hear them or feel them the way we do. There is a gulf we can appreciate and understand, but we cannot really cross it. That is why I cannot tell you what Taler is like. It would be a different world to you than the world it is to me.”

“I’d like to see it, though. Very much. I think I’d even like to live there.”

“I do not believe you would be happy there.”

“Why not?”

“Because non-Vegan immigrants are non-Vegan immigrants. You are not of a low caste here…On Taler you would be at the bottom.”

“Why must it be that way?” she asked.

“Because you see a white flower.” I handed it back.”

—This Immortal, from a conversation between a Vegan and human

I’m also partial to sensorium.

From the appendix of An Immense World: “There are some microbes that consist entirely of single cells and which also double as surprisingly complex eyes. Consider the freshwater bacterium Synechocystis. Light that hits one side of its spherical cell becomes focused on the opposite side. The bacterium can sense where that light is coming from, and move in that direction. It is effectively a living lens, and its entire boundary is a retina. The warnowiids, a group of single-celled algae, also seem to be living eyes, and each cell has components that resemble a lens, an iris, a cornea, and a retina.”

Of course, there’s substantial sensory variation even within a species. Here I’m assuming sensoria will cluster for a given species (which may or may not be true). So when I talk about “distances” between umwelten I’m speaking about distances between the centroids of these species-umwelt-clusters.

Also related is the longest sentence ever communicated by a non-human animal,by a chimp taught sign language. It uhh…had nothing to do with the finer points of philosophy: “Give orange me give eat orange me eat orange give me eat orange give me you." I doubt a lion granted speech would be that different. It’d just insert fresh gazelle for orange. (For the purposes of this piece I’m ignoring the differences in innate vocal learning ability between chimps and lions—chimps do have a leg-up in that regard.)

Which just happen to be like ours. I’m glad aliens converge on the symphony as an artform.

The Sapir-whorf hypothesis, put in the terms outlined here, amounts to the claim that soft umwelts have significant bearing on hard ones. Much of the evidence for this, however, seems relatively unconvincing to me, for arguments martialed in linguist John McWhorter’s book The Language Hoax: Why the World Looks the Same in Every Language.

Can an intelligent creature possess only a cognitive umwelt? Questions for further pondering. Or perhaps we’ll have to wait and see!

Love this. I've never encountered the connection between biological umwelten and culture, but of course the analogy is strong. Thanks for writing this!

Thanks for reading! I hadn’t much thought about the connection myself til I came across This Immortal. Good sci-fi often turns out to be really great at pumping intuitions haha